Updated Thursday at 5:35 p.m. ET

"Hitting a woman for a man is as normal as eating a tortilla from a food stand on the way to work," said Karen Paz, 34, from San Pedro Sula in Honduras, revealing a scar from a burn on her left shoulder. "He wanted to burn my face, but my daughter started screaming when she saw him taking the pan with boiling butter. She pushed him, and so he aimed for the arm instead."

Men can do anything to women in Honduras and the police hardly do anything about it, said Paz, while scrolling on her phone to show me more images of the burn and trying to find the police report she filed right after the attack.

"They detained him for only 24 hours, and then he came back home. I couldn't stay there anymore; the next time he was going to kill me. My daughter could not witness that," she said.

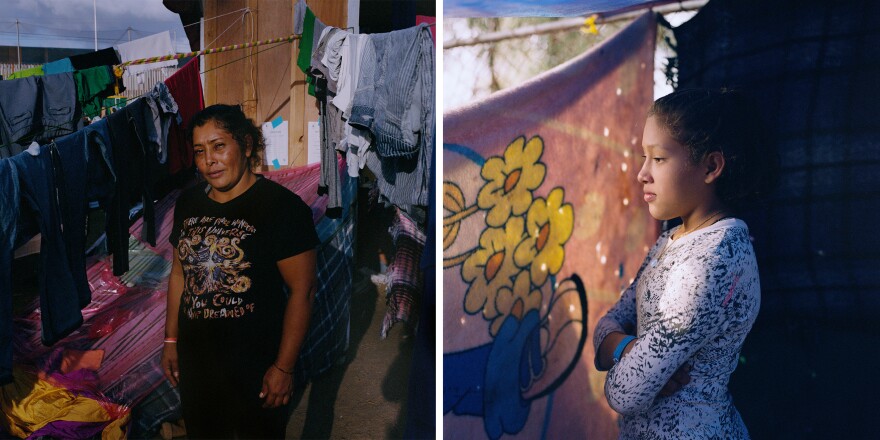

![(Left) Carmen Enamorado Alba, 31, is from Guaimaca, Honduras. (Right) Margarita Alberto Escobar, 39, sits with her children Dallana Michelle, 10, and Allan José Vargas, 12. They are from the Honduran town of Gracias. "The doctor told me [Dallana] may have had a cerebral edema as a result of the hit [from her father]. Then later she started convulsing with epileptic attacks," Escobar said.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/673adf5/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3000x1500+0+0/resize/880x440!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2019%2F01%2F16%2Fvalabrega-duo_edit_custom-e844a376097c2937a0c714bef14bfa8f50694754.jpg)

I met Paz near her tent inside the Benito Juárez Sports Center in Tijuana, Mexico, one of the sites where thousands of Central American migrants have taken shelter since arriving in two caravans in November 2018. Many of them had traveled the length of Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico on foot and on the occasional bus and truck ride since departing from San Pedro Sula, Honduras — one of the most dangerous cities in Latin America — in October.

Domestic violence was the leading reported crime in Honduras, according to a March 2015 report by the United Nations' special rapporteur on violence against women. Between 2009 and 2012, 82,547 domestic violence complaints were lodged in courts across the country. Yet a low percentage of domestic abuse charges result in a conviction. Honduras' special prosecutor for women cited far lower numbers in the 2012-2014 period: 4,992 registered complaints, but just 134 convictions, according to the U.N. report. The Migration Policy Institute found that El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, respectively, had the first-, third- and seventh-highest rate of gender-motivated killing of women in the world. Few of these cases are ever resolved by the courts.

![(Left) Maria Luisa Vasquez, 36, holds her children Brittany, 6, and César, 2. They are from Guatemala. (Right) Fanny Gabriela Regalado, 20, is from Honduras. "I felt very scared to report this [abuse], because at the time he had some link to a [gang]; I did not want them to hurt my family or my children. So I kept quiet," Regalado said.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/15939d8/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3000x1500+0+0/resize/880x440!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2019%2F01%2F16%2Fvalabrega-duo2_edit_custom-e9fda29cbb72c3f1541f613b59efd05cf692a99f.jpg)

Through my portrait series, from last Nov. 21 to Dec. 2, I documented Paz and 12 other women with their children who are survivors of domestic abuse and decided to flee their homes by joining one of last year's migrant caravans. For them it was a challenging, almost two-month journey to answer the question: What does it take for a Central American woman to give her children a better future?

I listened to these women's testimonies and decided to portray them not as victims but as their most resilient selves, for no abuse can measure up to the courage and strength it took to carry their children across multiple countries for a shot at a better life by asking for asylum in the United States.

At least one of the Central American women I met, Maria Lidia Meza Castro, 39, later managed to enter the United States — escorted by a group including two U.S. Congress members — and reportedly asked for asylum along with five of her children. With limited communication access, it is uncertain what has happened to the rest of those photographed for this series.

The Trump administration has tried to make it tougher for asylum-seekers escaping domestic or gang violence to gain protected status, although it has met challenges in federal court. In 2018, Syracuse University researchers said U.S. immigration judges rejected the highest number of asylum claims since at least 2001.

This week, as a new migrant caravan departed Honduras, President Trump repeated his controversial claim that"only a wall will work" to deter them.

There is a long wait south of the border. Most of the women and children I interviewed are asylum-seekers who are on a waiting list with more than 5,000 people. They initially took refuge at the Benito Juárez shelter, but many left for another site known as El Barretal. They were waiting in shelters for their turn to be heard, which could be months. Some of them started to think about crossing into the U.S. illegally instead of attempting to go through an official port of entry.

Whether they know it or not, reaching the U.S. border was only half the battle. They must now contend with an immigration system that has made it more complicated to have their case considered for asylum.

"I'm a survivor of violence already; I cannot bring my daughter back to go through that herself," said Paz. "I feel different here. I don't have someone who imposes his views and ways on me. I am not scared someone will come and attack me, like I used to be. I cannot go back."

Federica Valabrega is a documentary photographer based between Brooklyn, N.Y., and Rome. She reported and photographed this story in Tijuana, Mexico.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

![Mirna Yolanda Contreras, 29 (left), and Paola Arita, 32, are both from San Pedro Sula, Honduras. "Since we met in Puebla [Mexico], we have never separated. We became very good friends; we slept in the same place the whole time," Contreras said.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/c5086a4/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1999x2016+0+0/resize/880x887!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2019%2F01%2F12%2Fvalabregaf_1244_15dec18_14_custom-a8ee58068e01453a429c5c8a8c38bebcc0f7ae41.jpg)