When James Price walked into Samantha Cedillo’s office, he looked so nervous she thought someone had died.

But when he confessed his feelings for her, everything around her muted. She shuffled papers around on her desk, busying her hands while refusing to meet his eyes. As he continued to speak, his voice became muffled, drowned out by her anxious internal monologue:

This is the moment I’ve been trying to avoid.

She was conflicted because, despite the fact she reciprocated Price’s feelings, she knew a relationship with a man serving a life sentence for first-degree murder at the Omaha Correctional Center, where she worked as a programs coordinator, would not only be inappropriate, it would be illegal.

That charged moment beneath the fluorescent lights of her office in the prison library, on Nov. 22, 2021, began a forbidden relationship that led to a child conceived behind bars and a felony conviction for Cedillo. It would later reveal problematic cultural, reporting and investigative practices within the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, according to reviews of public records and interviews with former staff members.

Price and Cedillo’s prison romance made salacious headlines, but the pair have never publicly discussed the relationship nor birth of their child. Through a series of exclusive interviews over several months with Nebraska News Service, their relationship offers a rare look at the culture and consequences of love behind bars and, in this case, a child caught in the middle.

“They’re not just punishing us both,” Price said. “They’re also punishing my son.”

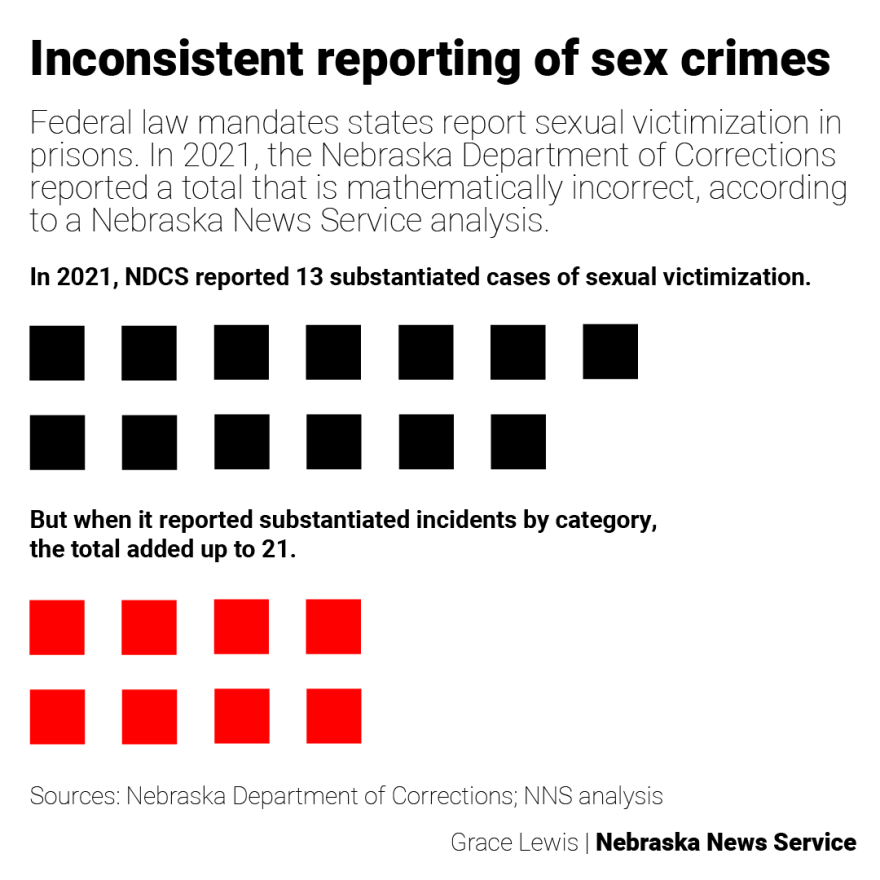

Errors in reporting leave scope of abuse unknown

By law, incarcerated people cannot consent to sexual contact with staff due to the inherent lack of power that comes with incarceration. Despite this, sex and relationships routinely occur in prison. A Nebraska News Service analysis found that, while systems exist to address the issue, their application within the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services seems inconsistent and inadequate.

“Unfortunately, they do happen,” said Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Director Rob Jeffreys during a question-and-answer session in March at the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. He added he was not aware of the Price-Cedillo case.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) of 2003 set national standards for prevention, detection and intervention of sexual abuse and harassment of incarcerated people, whether by staff or other incarcerated individuals. Since 2016, states must demonstrate compliance with PREA standards through mandatory federal reporting that is sent to the U.S. attorney general and available to the public online.

However, due to inconsistencies in Nebraska’s reporting, no one knows the full scope of the issue here.

A Nebraska News Service analysis of 10 years of Nebraska’s statewide Prison Rape Elimination Act victimization statistics found on the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services website uncovered mathematical errors in at least three of those years. In 2021, the survey, signed by the PREA Coordinator Danielle Reynolds, underreported the total number of substantiated incidents.

Also signed by Reynolds, the state’s 2017 Survey of Sexual Victimization contained inconsistencies that leave the actual number of staff sexual misconduct allegations unclear.

During a brief phone call in March, Reynolds said she would need department permission for an interview. In May, after four Nebraska News Service requests that the department authorize Reynolds to speak on the data inconsistencies, Dayne Urbanovsky, spokeswoman for the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, responded via email that the department was unable to dedicate additional time for follow-up questions.

On March 4, 2022, Karen Murray, Prison Rape Elimination Act auditor with KDM Consults, signed the final report for a facility audit of the Omaha Correctional Center. It said the facility exceeded expectations and had no allegations of, or investigations into, sexual misconduct by a staff member at that facility.

But when she signed that, the internal investigation into Cedillo’s relationship with Price had been underway for nearly four months, according to court records.

Murray told Nebraska News Service that if there was an ongoing case at that time, she would only have known about it if the facility reported it to her.

“I’ve been working with these guys now seven years,” she said. “They are very good at investigating false claims, third-party claims, anonymous claims, verbal claims, claims through the grievance procedure.”

Officials with the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services declined repeated requests to discuss the inconsistencies.

“Responding to follow-up questions for individual stories is beyond the scope of what we can accommodate,’’ Urbanovsky wrote in an email in April. “NDCS is responsible for the safe management of incarcerated individuals as well as staff members. It is a 24/7 operation that requires constant attention from our facility staff, our wardens, deputy directors and Director Jeffreys.”

But when the Nebraska News Service checked the department’s website about two weeks after questioning officials about data inconsistencies, those reports were removed from the government site.

It remains unclear why the reports are no longer publicly available. However, Nebraska News Service obtained and archived the documents before they were removed and is publishing them alongside this story so the public can still access them. View the original documents here.

Workers: us-versus-them mentality

While unanswered questions remain about reporting inconsistencies, Cedillo faced a different kind of uncertainty — how to navigate her feelings for an inmate in a workplace where she felt increasingly isolated and unsupported.

From 2018 to 2020, Cedillo worked as an administrative assistant to the Omaha Correctional Center Wardens Barb Lewien and Rick Cruickshank. She said she enjoyed the work and felt supported there.

After a year-long hiatus from correctional work, Cedillo returned to the Omaha Correctional Center in 2021, as a non-clinical programs coordinator. There, she found the work in the so-called “back of the house” to be a different environment, she said.

And then she met Price.

Cedillo said she knew she was headed for trouble, falling for a convicted murderer.

Nebraska Department of Correctional Services employees undergo training that stresses the importance of keeping things professional and details the consequences of inappropriate relationships with inmates.

But Cedillo said she struggled to reconcile her emotions and couldn’t find any institutional support for help or guidance.

“If I’d had the same type of loyalty and feeling of support and pride and sense of integrity that I felt when I first started in non-clinical programs — by the people surrounding me, including the wardens I had so much trust and love in, if I had had that same type of support — never would I have allowed Tank and I to happen,” Cedillo said, using Price’s nickname.

In her new role, she worked directly with inmates and correctional officers and said she became disillusioned after witnessing the dehumanizing treatment of incarcerated people.

“This is not fitting what I always respected and viewed corrections to be,” Cedillo said.

Former corrections staff, inmates and experts described an “us-versus-them” culture between the incarcerated people and prison staff. Cedillo said she came in hoping to do her job well, make things more efficient and expand access to programs for the incarcerated. But she said her efforts were repeatedly blocked. The librarian at the time, Jane Skinner, confirmed that it was difficult to get programs up and running.

Cedillo said staff routinely failed to prioritize access to the library and programs, often canceling them despite sufficient staffing, so she, Skinner and another coordinator often stayed late to ensure that inmates had access to the library and programs.

Cedillo and Amy Jacoby-Loftis, a former social worker for the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, both said they were taunted and called names by coworkers for showing compassion toward prisoners.

She said she came to admire and respect Price for his ability to hold his head high in that environment — especially as she began to feel increasingly isolated, unsupported and unprotected by coworkers who often ignored inmate harassment directed at her.

Cedillo said she realized she loved Price when his mere presence defused a situation where an aggressive prisoner made her fear for her safety.

“He just has this energy about him that demands respect,” she said of Price.

It wasn’t the only time Cedillo noticed Price looking out for her. Incarcerated men often yelled slurs at her as she walked through the yard, but sometimes it was unusually quiet — then she’d realize Price was walking 10 feet behind her, she said.

A review of incident reports, which Cedillo provided to Nebraska News Service, show that she brought her claims of harassment to the attention of her supervisors.

According to one report, a coworker ignored an altercation on March 15, 2022, between Cedillo and two prisoners who she said made her fear for her safety. A corrections corporal saw the incident and looked the other way, even when Cedillo radioed for assistance, she said during a Nebraska News Service interview and in her incident report.

“At no point did [the corporal] stick up for me, speak up in support or as assistance and both inmates actually seemed more empowered with him there because of his lack of show of force and presence to a fellow staff member,” Cedillo wrote in her incident report.

She said the general response from her coworkers was that this treatment was to be expected as a woman in corrections.

In prison since 19: Life behind bars

In a separate interview, Price said his feelings for Cedillo first grew from the way she treated him: with fairness and kindness.

As a lifer, Price said he knew his odds of getting out and starting the family he dreamed of were slim to none.

On July 22, 1995, Price, along with seven others, confronted 18-year-old Curtis Patterson, outside an Omaha home, forced him into a van at gunpoint and drove him to a dirt road in North Omaha. There, they forced Patterson to lie on his stomach, kicked him and demanded information about stolen property while Price aimed an AR-15 style rifle at him, according to court records. Price then ordered Patterson into the trunk of a car and fired a shot that killed him, before driving the car behind an apartment complex and setting it on fire.

A jury convicted Price, then 19. A judge sentenced him to life in prison without parole for felony murder in the first degree, plus five to 10 years’ imprisonment for using a firearm to commit a felony. Price lost an appeal in 1997.

Price said his early experience in corrections was rough.

For the first 15 years, he said he was angry, impulsive and disrespectful. His attitude landed him a long stint in segregation, during which he said he reflected and realized he needed to change. He began throwing himself into educational and rehabilitative programs, he said.

While at the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln, he was a part of a Prison Fellowship Academy program for a year, graduated and stayed on as a mentor and facilitator for another five years before Rich Cruickshank, who was the warden of the Omaha Correctional Center at the time, asked Price to transfer to the Omaha Correctional Center to help start up a similar program there.

Mutual respect, unexpected bond

Price was already working as a library clerk at the Omaha Correctional Center and heavily involved in programs when Cedillo started working there again. When the position opened for the programs clerk — a type of assistant who sets up for programs, creates flyers and helps promote programs to encourage others to sign up — she said Price was the obvious choice because he was knowledgeable about programs and was a respected and trusted member of the incarcerated population.

Cedillo said coworkers told her that Price was the person to go to if she ever had questions about programs and wanted a prisoner’s perspective.

“They would never admit it, but there’s an unspoken trust with lifers,” Cedillo said.

She said most men sentenced to spend their life behind bars come to carve out a purpose for themselves on the inside and don’t want to cause trouble in the place they will likely live forever.

Cedillo said she took the advice, and she and Price had many conversations about prison programs, what Price thought could be better and the obstacles he faced to make the programs better.

As they worked closely together, Cedillo and Price said they were always appropriate in their interactions with each other until that night in 2021.

Cedillo said she tried to suppress her feelings and dove into her spirituality for guidance, meditating on what to do. She said she made a conscious effort to avoid anything that could be seen as unprofessional — she even avoided touching him. When she handed him something, she would nearly let the item drop before he had a grip on it, she recalled.

When Price approached her that night, she had just returned to work from a Buddhist silent meditation retreat and was feeling more in touch with what she believed to be right, viewing Price as a man rather than just a prisoner, she told Nebraska News Service during a four-hour interview at her Iowa home in March.

“All of those things were very conflicting in my mind when he came into my office that night,” Cedillo said.

When she finally looked up, he saw tears in her eyes, Price said. She told him she felt the same way.

They set clear boundaries for the budding relationship, Cedillo said. She told Price she would never bring anything into the prison for him or anyone else. Price said he agreed and would never ask her to.

They also agreed to keep the relationship nonphysical — both to minimize risk and because they wanted it to be built on emotional connection rather than physical intimacy, Cedillo said.

“We wanted it to be as pure as we felt it to be,” she said.

Prison staff monitor the relationship

Others in the prison had begun to suspect there was more to their relationship.

In November 2021, “confidential informants” reported that Cedillo had an inappropriate relationship with Price, according to the criminal complaint filed against Cedillo in Douglas County on March 1, 2023. It is unclear if their relationship was reported before or after it actually began on Nov. 22, 2021.

Price said suspicion arose even before he and Cedillo acknowledged their feelings for each other. He said other inmates questioned how he’d earned staff trust, and Cedillo said programs coordinators like herself were warned they’d be under scrutiny following recent notable staff misconduct cases. She said even before she and Price became involved, she had been falsely accused of having sexual relationships with other incarcerated men and also of bringing in contraband to the prison. She denied doing either.

“All the females in corrections were getting that pressure, especially program coordinators,” Cedillo said.

According to dates provided in the criminal complaint, it took five months of internal review after their suspected relationship was reported before a criminal investigation was opened.

During that time, Omaha Correctional Center employees collected video footage and kept track of how much time the two spent alone together. Meanwhile, Cedillo and Price’s relationship grew more serious, and the two eventually had sex and conceived a child in March 2023.

Price, now 49, and Cedillo, now 33, both wanted children before they became intimately involved, they said in separate interviews with Nebraska News Service.

During a conversation about what Price would do if he wasn’t incarcerated, they discovered their mutual desire to have a child.

In keeping with their nonphysical agreement, they started trying to conceive nonsexually — Cedillo would go to a prison bathroom and insert Price’s sperm when she was ovulating — in January 2022.

But by March they still weren’t having any luck getting pregnant, so they had sex a handful of times in her office at the prison library in late March, she said. Cedillo said she sensed the department was onto them, and that they might be running out of time to get pregnant.

Deputy Warden Shawn Freese, Cedillo’s direct supervisor at the Omaha Correctional Center, began warning her about the investigation into the relationship, she said, and he required her to file reports when she was alone with Price. Cedillo said she continued spending time with him even though she knew they were being watched because she no longer felt any loyalty toward the people she worked for.

Nebraska State Patrol takes over investigation

Cedillo resigned on March 30, 2022. She said Freese called her into his office to let her know the investigation was nearing a conclusion. At the same time, she said, she wasn’t feeling fulfilled professionally because so many of her efforts to help inmates were being blocked, so she agreed to resign.

Less than a month later, Nebraska State Patrol investigator C.J. Alberico was assigned to investigate Cedillo, according to Alberico’s affidavit included in the criminal complaint filed against Cedillo.

In July 2022, Alberico interviewed Cedillo, who brought up the lack of response to her safety concerns. In the affidavit, Alberico dismissed the statement, noting that it didn’t match what Cedillo wrote in her incident report that served as her letter of resignation.

But according to Cedillo, she didn’t write that report freely. She said Freese made her write it by hand in his office while he dictated what it should say. A review of Cedillo’s previous incident reports showed she usually typed lengthy and detailed reports, unlike the three-sentence resignation letter, which was handwritten.

Freese declined a Nebraska News Service request to comment on this story.

“NDCS policy does not permit team members to speak on behalf of the agency, facility, division, or program,” he wrote in an email in May.

Nebraska News Service filed a public records request for Cedillo’s personnel records, as well as for the investigative file of the criminal case. The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services and the Nebraska State Patrol both denied these requests, citing state law.

‘He was sobbing’

After Cedillo resigned, she and Price had free rein to communicate through official channels for almost a year. Inmates are typically allowed tablets with 24-hour access to messaging services and video visits during approved hours. They can also make phone calls during approved hours.

But Price said he was speaking to Cedillo on an illegally obtained cellphone when they found out she was pregnant, just weeks after she resigned.

Price said he is not proud of the fact that he had a cellphone and takes responsibility for breaking prison rules. His possession of the cellphone led to his transfer back to the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln, where he remained for just over a year.

While they spoke, Cedillo messaged Price a picture of the pregnancy test she’d taken. Price asked her what it was, and she explained it was a test that said she might be pregnant.

Cedillo took four pregnancy tests while remaining on the phone with him. The third test displayed the word “positive.” The fourth said “pregnant.”

Finally convinced, Price said he shoved his head into the pillow and bawled like a baby.

“He was sobbing,” Cedillo said. “I could hear it on the phone.”

Price was overjoyed.

Cedillo, on the other hand, had some decisions to make.

She said she knew there was an investigation into her misconduct — and that without a child carrying Price’s DNA, officials would have no hard evidence against her. But Cedillo wanted a child, and she felt she couldn’t take away what might be Price’s only chance to become a father. He deserved to have a child, she said.

“I chose him because I knew that he would be a good father,” Cedillo said.

She sent Price her listing on a baby registry through official prison communication channels. That registry tipped off Alberico, the state patrol investigator, to the pregnancy, according to court records.

The day after their son was born, investigators obtained a warrant for the baby boy’s DNA.

On March 2, 2023, Cedillo was arrested on a felony charge of sexual abuse of an inmate — three months after she gave birth to their son.

When Nebraska News Service asked the Nebraska State Patrol about the investigation, officials directed a reporter to submit a formal public records request. That request, which was the second Nebraska News Service filed regarding this case, was denied.

Once Cedillo was arrested and her court case began, she and Price could no longer communicate due to the ongoing case.

Cedillo pleaded no contest to a reduced charge of attempted sexual abuse of an inmate and was found guilty. Price said he wrote a letter to the judge vouching for her character and asking for leniency — not only for their son’s sake, but because he believed she didn’t deserve jail time.

Department communication ban

On Feb. 20, 2024, Cedillo was sentenced to three years of probation and was required to register as a sex offender. She said this made finding work difficult, but she finally has a steady job and is able to provide for their son. With the closure of Cedillo’s criminal case, her communication with Price resumed.

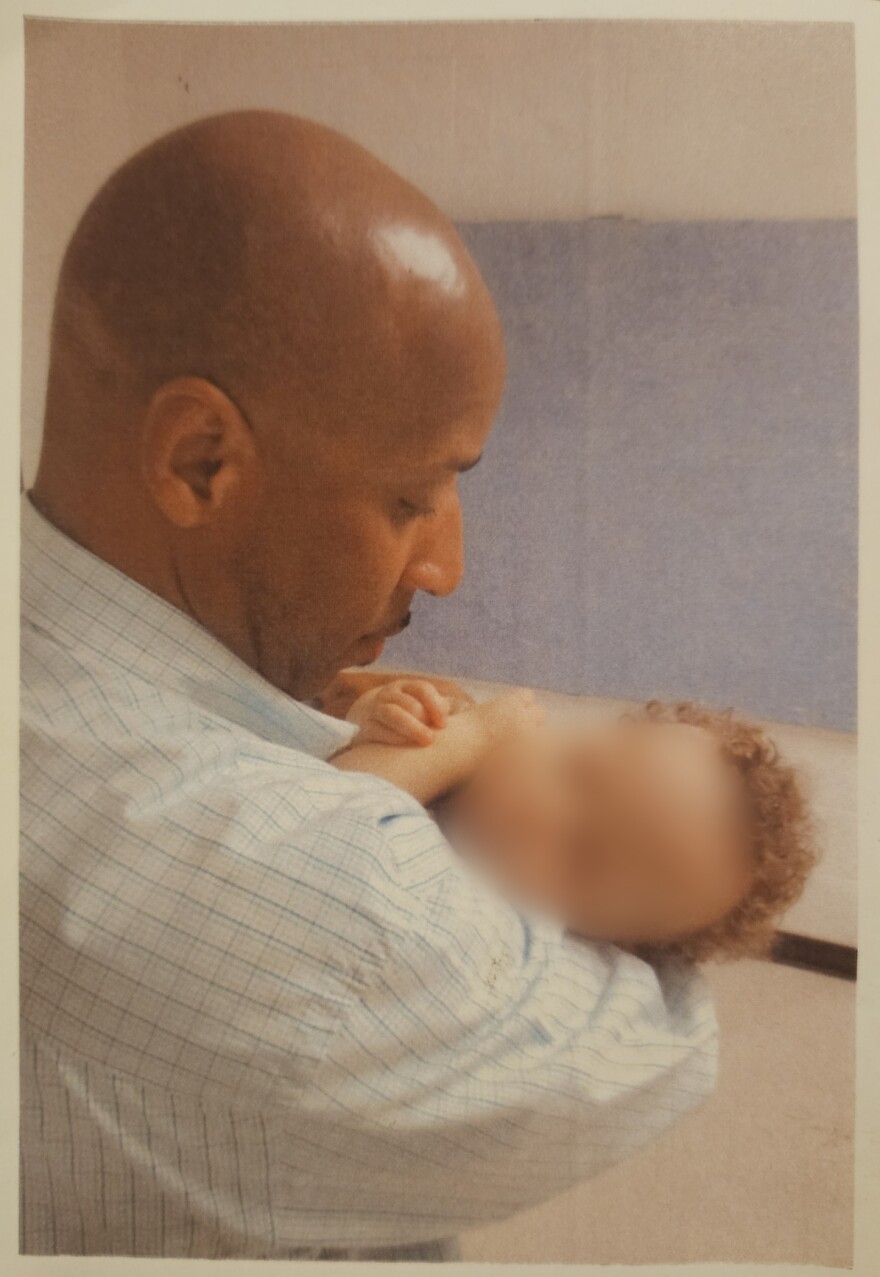

It was then that Price met his 1-year-old son.

Less than a week later, Warden Barb Lewien, recently transferred from the Omaha Correctional Center to the Nebraska State Penitentiary where Price was incarcerated, cut off all communication between Price and Cedillo.

Lewien declined an interview request from Nebraska News Service and did not respond to two subsequent email requests for comment.

According to Price, the department cited security concerns and his status as a Prison Rape Elimination Act victim as reasons for the ban — though he feels they treat him like the perpetrator.

In emails provided by Cedillo, Lewien wrote that, as warden, she held final authority to suspend calling and e-messaging privileges to ensure the “safety, security and good order” of the facility, its staff and inhabitants. She later wrote that Cedillo’s policy violation and felony conviction “does strongly indicate concern for the safety, security and good order of the facility, its team members and population.”

Price argues that all communication is monitored, and Cedillo poses no threat. While inmates can’t contact parolees, probationers like Cedillo aren’t usually barred.

Probationers, on the other hand, typically are restricted from having contact with those who have criminal records, but Cedillo’s judge made an exception for her contact with Price. The judge’s sentencing order directs Cedillo to avoid contact with those with criminal records or who are on probation or parole, “not including James Price.”

Price and Cedillo see the judge’s exception as evidence that the judge did not perceive Cedillo to be a safety or security threat to Price and understood the importance of their communication for the purposes of co-parenting.

Danielle Jefferis, assistant professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Law, said that the judge’s exception does not bind the prison, though it is evidence that the court overseeing Cedillo’s case does not see an issue with their communication.

Prisons, however, have a history of resisting court directives about their operations, Jefferis said.

She explained that courts give prisons significant deference because running a prison is considered extremely challenging, with many complex moving parts and financial pressures.

Price and Cedillo argue that the lack of oversight enables department leadership to punish them beyond the courtroom — at the expense of their son.

Price fights for co-parenting rights

While Price and Cedillo are no longer in a romantic relationship, they both said they are committed to co-parenting their child.

Price is suing the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, its director, Rob Jeffreys, and Lewien, alleging retaliation and constitutional violations regarding visitation and communication. Without a right to counsel in civil cases, Price is pursuing the case alone, using a prison litigation guidebook, he said.

Since filing the lawsuit, Price said he’s faced repeated misconduct reports for alleged unauthorized communication with Cedillo. Price said within the last two years, the only misconduct reports he’s received have been regarding his communication with his son and Cedillo.

These led to lost privileges, including removal of his brother’s phone number from his contact list and a month-long suspension of tablet access — his only way to message or video chat and the primary means of filing grievances.

Delays in receiving paper grievance forms hindered his appeals, which he included in his second amended complaint filed in the district court of Lancaster County in April 2025. From March 4 to April 2, Price was allowed one 15-minute phone call a day and spent half of them speaking with Nebraska News Service about his circumstances. Typically, inmates are allowed two hours of phone time each day in addition to messaging and video visits on their tablets, Price said.

Jefferis said retaliation is a prevalent issue in prisons, especially when incarcerated people sue.

In October, Price was transferred to the Tecumseh State Correctional Institution in Johnson County, Nebraska.

In an email obtained from Cedillo, dated Oct. 3, 2024, Nebraska State Penitentiary Unit Administrator Kimberly McGill said Price was transferred to Tecumseh because it is the least restrictive environment for his custody level.

Price said he believes the move was punitive. The rural facility’s location and staffing shortages generally make visits difficult for prisoners.

Price’s toddler needs an adult to take him into the visitation room. Cedillo, barred from contact, must rely on Price’s brother and his brother’s girlfriend, who live in Lincoln, to meet her near the facility to take the child in to see Price. With Tecumseh an hour away from Price’s family, aligning everyone’s schedules to meet there is difficult. Price’s visits with his son dropped from weekly to less than once a month, he said.

“That’s why being able to talk on the phone with [our son] or do video visits, or anything like that is so important because these physical visits just can’t happen,” Cedillo said.

‘Takes me away from here when I see his face’

The ban on communication with Cedillo limits Price’s ability to be a father in a number of ways, he said. He can’t discuss his son’s development with Cedillo, receive photos or videos or stay informed about the toddler’s day-to-day life. When their son was rushed to the emergency room for an allergic reaction, Price didn’t find out until more than a week later, he said.

Price said the 2-year-old boy loves to be read to. During their physical visits, he’ll crawl into Price’s lap, and the two will eat snacks and read Dr. Seuss and Paw Patrol books. Every so often, the toddler will sneak a peek underneath the paper towel on the table — Price’s hiding spot for his son’s favorite snack, a chocolate-chip cookie that they split at the end of the visits.

“I really can’t even express into words how much I love the two of them,” Price said. “It just takes me away from here when I see his face.”

Those moments are fleeting.

Cedillo said the toddler is getting to a place developmentally where he notices his father’s absence and misses him.

“[Our son] is starting to understand the concept of a dad,” she said.

A Photoshopped picture of Cedillo, Price and their son sits in the 2-year-old’s bedroom. Cedillo said that when it has been a while since he’s seen his dad, he’ll point to it and ask about “Dadduh.”

Their son lights up at sights and sounds he associates with seeing his dad — like crossing the bridge from Iowa into Nebraska. When his grandfather used to answer Price’s calls, and the recording said, “Hello, this is a prepaid call from James, an inmate at the Tecumseh State Correctional Institution,” the toddler would gasp and run in circles, shouting, “Dadduh-dadduh-dadduh!”

When the call ended, the toddler would burst into tears.

Price said his primary concern is for his son and their ability to help him grow.

“[My son] can have something I never had, something I’ve dreamed of giving him from the day he was born,” Price said. “He can have his father in his life.”

Price grew up without his biological father, and he said that absence contributed to poor decision-making in his youth.

“I do not equate not having my father actively in my life as the reason for my failures,” Price said in his letter to Cedillo’s sentencing judge. “My actions were of my own accord, and I take full responsibility for the mistakes I’ve made. My sentence of life is a daily reminder for the pain and harm I caused my victim, his family and all those who were affected by my ignorance. No amount of time could have been imposed upon me that would make up for the destruction, or walk back the harm I caused.”

Price said that he can’t bring back his victim, no matter how much he wants to. While it doesn’t restore the life lost, Price said one thing he hoped he could do was bring another life into the world:

“I believe [my son] is a big part of my giving back to the world,” Price said.

Nebraska Behind Bars

This story is part of a series produced by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Journalism and Mass Communications 2025 in-depth reporting class.

The Midwest Newsroom is an investigative and enterprise journalism collaboration that includes Iowa Public Radio, KCUR, Nebraska Public Media, St. Louis Public Radio and NPR.

There are many ways you can contact us with story ideas and leads, and you can find that information here.

The Midwest Newsroom is a partner of The Trust Project. We invite you to review our ethics and practices here.

![The 2-year-old son of James Price and Samantha Cedillo chases a red soccer ball at his Iowa home on April 9, 2025. The child was conceived while his father, Price, was an inmate at the Omaha Correctional Center and his mother, Cedillo, worked as a programs coordinator there. “I believe [my son] is a big part of my giving back to the world,” Price told a journalist.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/63bf8b3/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1763x1175+0+0/resize/880x587!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F03%2F44%2F4e7d12f748c5a7e7ebe34d6b28e3%2Ffifth.jpg)