Protesters were arrested over the weekend after throwing mashed potatoes on a Claude Monet painting hanging in a German museum, the latest recent example of activists defacing (albeit briefly) famous artworks in order to draw attention to the existential threat posed by climate change.

The Barberini Museum in Potsdam said on Sunday that the painting itself — Grainstacks, which dates back to 1890 and is valued at $110 million — was protected by sealed glass and remains unharmed, though the 19th-century gold frame was damaged.

"We are in a climate catastrophe, and all you are afraid of is tomato soup or mashed potatoes on a painting," is the English translation of what one of the two members of the German climate group Letzte Generation said as they knelt underneath the dripping painting with their hands glued to the wall. "I'm afraid because the science tells us that we won't be able to feed our families in 2050 ... This painting is not going to be worth anything if we have to fight over food."

We make this #Monet the stage and the public the audience.

— Letzte Generation (@AufstandLastGen) October 23, 2022

If it takes a painting – with #MashedPotatoes or #TomatoSoup thrown at it – to make society remember that the fossil fuel course is killing us all:

Then we'll give you #MashedPotatoes on a painting! pic.twitter.com/HBeZL69QTZ

The museum has since announced that it will be closed until Sunday in order to discuss the incident and security measures with its national and international partners to "jointly set the course to preserve art and cultural assets for future generations."

"The attack on a work of the Hasso Plattner Collection as well as previous attacks on artworks, among others in the National Gallery in London, have shown that the high international security standards for the protection of artworks in case of activist attacks are not sufficient and need to be adapted," Director Ortrud Westheider said in a statement.

The mashed potato protest came roughly a week after activists from the British environmental group Just Stop Oil pulled a similar stunt at London's National Gallery, dumping cans of tomato soup over Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers in order to protest fossil fuel extraction.

Just as in Germany, the duo was arrested, and the museum said only the frame — not the painting itself — suffered minor damage.

🌻🥫 BREAKING: SOUP THROWN ON VAN GOGH’S ‘SUNFLOWERS’ 🥫🌻

— Just Stop Oil ⚖️💀🛢 (@JustStop_Oil) October 14, 2022

🖼 Is art worth more than life? More than food? More than justice?

🛢 The cost of living crisis and climate crisis is driven by oil and gas.#FreeLouis #FreeJosh #CivilResistance #A22Network #JustStopOil #NoNewOil pic.twitter.com/18T2zSP2ws

Just Stop Oil had already gained visibility for its public acts of protest, with members gluing themselves to gallery walls and blocking roads and racetracks. It's one of several environmental activist groups that have carried out such art attacks in recent months, raising both awareness and controversy.

In May, a man disguised as an old woman in a wheelchair threw a piece of cake at the Mona Lisa, shouting at people to "think of the Earth" as he was escorted out of the Louvre Museum in Paris. In July, Italian climate protesters glued their hands to the glass covering Sandro Botticelli's Primavera in Florence's Uffizi Gallery. Around the same time, members of Just Stop Oil stuck themselves to the frames of famous works in London, Manchester and Glasgow, and spray painted "No New Oil" under a copy of Da Vinci's The Last Supper.

None of the paintings themselves were permanently damaged — the largely symbolic demonstrations are intended not to destroy the art, but rather to ramp up public pressure on governments to halt destructive new fossil fuel licensing and production.

Phoebe Plummer, one of the Just Stop Oil activists who threw the tomato soup, said in an interview clip circulating on social media that the group wouldn't have considered taking such an action if they didn't know for a fact the painting was protected by glass. She added that the point isn't to ask whether people should be splashing soup on paintings, but to raise more urgent questions about fossil fuels, climate policy and the real humanitarian costs.

"We're using these actions to get media attention because we need to get people talking about this now," she says. "And we know that civil resistance works. History has shown us that it works."

Climate activists aren't the first to target famous artworks as sites of public protest. Here are three famous examples from over the years.

The slashing of the Rokeby Venus

The Toilet of Venus, nicknamed The Rokeby Venus, is one of the most famous works — and the only surviving nude — by Spanish painter Diego Velázquez. It shows the Roman goddess of love lying naked on her side, with her back to the viewer, gazing into a mirror held up by Cupid.

In March 1914, a suffragette named Mary Richardson walked into London's National Gallery and slashed the painting several times with a meat cleaver, slicing across Venus' back and hip.

Richardson, an art student and journalist, did so as a deliberate act of protest against the arrest of British suffrage leader Emmeline Pankhurst. She later said she had chosen that particular work both because of its value and "the way men visitors gaped at it all day long."

"I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history," she said.

Richardson was sentenced to six months in jail but released after several weeks following a hunger strike. The museum closed for two weeks while its restorer repaired the painting, which is still on display today.

It was far from Richardson's only controversial act. Citing scholar Julie Gottlieb, Artsy.net explains that she was a noted arsonist who was arrested for civil disobedience on nine occasions — and whose politics took a dark turn.

After women won the right to vote, Richardson went on to join the fascist Blackshirts group and create the National Club for Fascist Women in London. She was reportedly expelled from the British Union of Fascists in 1935 for her feminist advocacy.

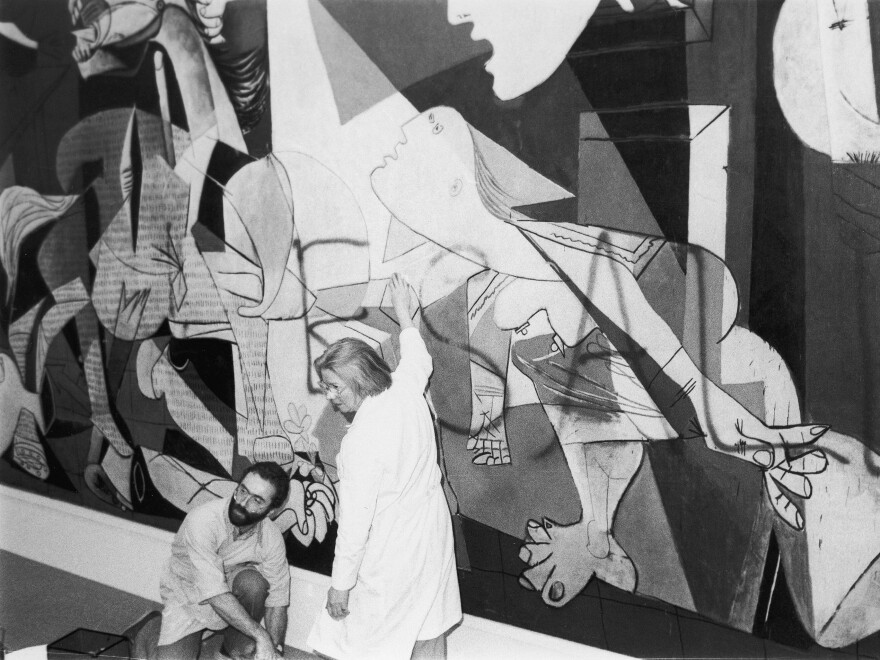

Guernica vandalized during the Vietnam War

Pablo Picasso's Guernica, one of the most famous anti-war works of art, became the site of one such protest during the Vietnam War.

In February 1974, a year after Picasso's death, Iranian artist Tony Shafrazi produced a can of red spray paint from his pocket and wrote, "Kill Lies All" in massive letters across the black-and-white painting as it hung in New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Shafrazi, a member of the Art Workers' Coalition, was reacting to President Richard Nixon's pardoning of William Calley, who was the only U.S. Army officer to go on trial for the My Lai Massacre of 1968. He also said he was trying to reactivate Guernica as a cry of protest against war and civilian deaths, according to Spain's Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

Shafrazi was led away from the scene and charged with criminal mischief. When asked by police why he did it, Shafrazi said "I'm an artist and I wanted to tell the truth," according to The New York Times.

The words he spray-painted reportedly alluded to a quote from the book Finnegans Wake by James Joyce: "Lies. All lies."

Technicians and conservators were able to erase the red lettering within an hour, using an organic solvent and surgical scalpels. Because the painting had been coated in a heavy varnish some years earlier, it did not suffer permanent damage (that coating had to be removed and was later replaced).

Shafrazi, who is now a prominent art dealer in New York, was greeted with a giant Guernica-inspired cake at an exhibit afterparty in 2008, and reportedly scrawled "I'M SORRY – NOT!" on it in red icing. When asked whether he would recreate the 1974 incident, if given the chance, Shafrazi told Vulture:

"Oh, it was a different time, you can't talk about it that way," he said. "It was a miserable time, and there was a need to be addressed. I was 30 years old. Many, many elements make that particular moment unique. I wouldn't be that person now, of course not."

Targeting museums with ties to opioid makers

In recent years, members of a drug policy group have held public demonstrations at prominent museums with financial ties to the Sacklers, the family that owns OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma.

PAIN (which stands for Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) was founded in 2017 by American photographer and activist Nan Goldin, who herself recovered from a yearslong addiction to the powerful painkiller. The group aims to hold the manufacturers of the opioid crisis accountable, and initially focused mainly on what it calls the "toxic philanthropy of the billionaire Sackler family."

They've specifically pushed museums, universities and other institutions that have long accepted donations from the Sacklers to cut those financial ties and remove the family's name — which for many years was not widely recognized — from their buildings.

A large part of their strategy has been to protest publicly and creatively at those very institutions.

In March 2018, activists unfurled banners and scattered pill bottles (labeled "OxyContin" and "prescribed to you by the Sacklers") inside the Sackler wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, before lying down in a symbolic "die-in."

The following February, protesters at New York's Guggenheim Museum dropped thousands of slips of paper designed to look like OxyContin prescriptions into the central rotunda from above. Goldin said it was in response to a recently disclosed statement by a Sackler family member who said years ago that OxyContin's launch would be "followed by a blizzard of prescriptions that will bury the competition." Then they marched down Fifth Avenue and continued their protest on the steps of the Met.

That July, the group worked with French anti-opioid activists to stage a protest at the Louvre, which at the time had a "Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities." They stood in the pool next to the iconic glass pyramid holding a banner that read, "Take down the Sackler name," and also staged a die-in on the plaza.

The group conducted similar demonstrations at London's Victoria and Albert Museum and the Harvard Art Museum, as well as outside of the New York courthouse where the company's bankruptcy proceedings took place last year.

The Louvre became the first major museum to remove the Sackler name from its walls in July 2019. Since then many other museums, including the Met and the Guggenheim, have distanced themselves from the family. In London, the National Gallery, Tate museums, Serpentine Galleries, British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum have taken similar steps. Several have pledged to stop accepting donations from the family.

"Direct action works," Goldin said after the Guggenheim renamed its education center in May of this year. "Our group has fought for over four years to hold the family accountable in the cultural realm with focused, effective action, and with tremendous support from local groups that fought by our side."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.