A woman with dark hair and wearing comfy sweats sits at her kitchen table in Des Moines. She sips her coffee and rearranges some books on her table.

Her name is Sonia Reyes. She was working from home that day because she simply didn’t feel well enough to head in to the office. She has fainting spells and sometimes doesn’t feel comfortable driving. She had just finished an online class for her bachelors degree in Intercultural Communications.

"Today is a very bad day," she admits. "I am extremely dizzy, my blood pressure is very low so I am not able to leave the house because I faint randomly. So I'm homebound today."

Reyes has suffered from these long-term COVID-19 symptoms for almost two years. She first tested positive for the virus in July of 2020, after testing negative three times. She says the most serious symptom, her low blood pressure, is the most difficult and has affected her life in so many ways. She has even fainted in public when she couldn't decipher her body's warning signal fast enough.

Reyes was one of the many Latinos who ended up being hospitalized with the virus. At one point last April, ICU doctors at the University of Iowa noticed about 90 percent of the patients there were Hispanic. And a lot of them only spoke Spanish. Many were treated and eventually sent home. But that’s not the end of the story.

“We started getting calls about the problems that they were having. After they were discharged from the hospital," pulmonologist Joseph Zabner said.

He works within the Post-COVID-19 Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics and created its Spanish-speaking team of medical experts. The clinic is designed to treat people with lasting COVID symptoms, like Reyes. It's the only clinic in the state and one of the first in the country devoted to treated patients who have recovered from the virus, yet still face long-term symptoms. About half of the leading medical team members are Latino.

Although Zabner said there aren’t many Latino patients at the clinic yet, that doesn’t mean they aren’t experiencing long-term symptoms. It could be a problem of access. There are people coming from all over the Midwest seeking care for their long-term symptoms. But all of those people had the capacity to travel.

“I would assume it's access. The ability to come from rural communities to Iowa City, insurance, things that are beyond the control of the physicians and perhaps it’s because they do not know about it," Zabner said.

He continued by adding for some, access may be even more complicated when it comes to finances and immigration statuses.

Reyes has relied heavily on the word-of-mouth strategy. She didn’t know about the clinic until a friend told her. Then she told her stepfather, who was also experiencing symptoms.

She considers herself fortunate because she does have family and friends who can take her to her clinic appointments, she has insurance and she's bilingual. But not everyone in Iowa's Latino communities have these assets.

"Any community that is historically marginalized, or minoritized, they don't feel confident in advocating for themselves. One, because they are living in survival mode most of the time. And also they don't know there are resources," Reyes said.

They are told no a lot of the time. So you give up after a while, because you have to pick your battles and know where you're going to put all of your energy towards.Sonia Reyes

She added that she has found the Post-COVID-19 clinic has also helped her in her school life. The clinic provided her with a medical reason as to why it was difficult for her to come to in-person classes. Again, another aspect some who are required to go to in-person work aren't afforded if they don't have access to the clinic or know about it.

Reyes said the clinic helped her feel validated: "There were times when I started to question myself, whether I was making up the symptoms in my head, especially the brain fog."

"Brain fog" is one of the more common long-term effects of COVID-19, according to Zabner. It's when someone's thinking feels sluggish and they suffer from forgetfulness.

Another Information Access Issue

It’s not only knowledge of the Post-COVID-clinic some Latinos don’t have access to. Medical experts have noticed a disparity still exists between Latinos and Spanish speakers and access to valid information about the virus and its vaccine.

"That's one of the tasks that we probably have to figure out how to solve these year," Zabner said.

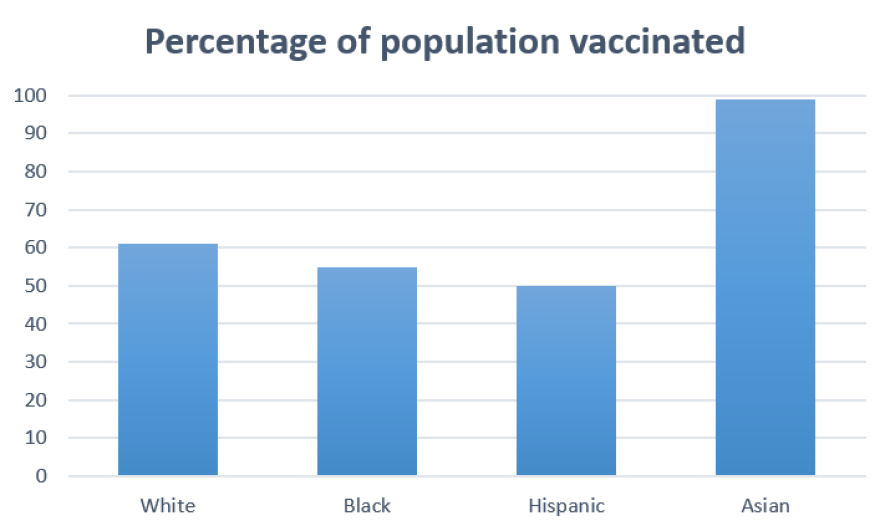

The Hispanic population in Iowa is the lowest-vaccinated group, according to a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation. And some attribute that to a lack of outreach efforts. Like Ramon Calzada.

He said he feels like state officials are rushing to return to normal, when his community can’t do that yet. He said people need COVID-19 resources and information—not because it has necessarily changed, but because they never got the right information to begin with.

Zabner agreed, saying he has noticed many people are getting the wrong information about the virus and the vaccines available to protect people from it.

"Misinformation has been rampant, not only in Spanish, but in English and everywhere. And we'll hopefully learn from this, there'll be other pandemics and we'll learn that we need to be prepared and we need to figure out how to manage the information," he explained.

At first, Calzada said, the biggest problem was making sure Latinos had access to vaccines. Now there’s plenty of vaccines available. And people are going back to “normal.” Even though he said the state’s Latinos are not ready to be back to normal.

“Now that we have the opposite, and now that people see that we're sort of going back to normal, even though we're not really going back to normal, but people's perception is that we're going sort of back to normal. And so now [they are] like, 'Oh, okay, so maybe I don't need a vaccine.' So now it's a different monster to attack, you know, it's a monster of misinformation," Calzada said.

He lives in Council Bluffs where he directs a social service office called Centro Latino of Iowa. And he said one problem he has noticed is that it seems to him the state still needs to work on that monster. He said it’s delegating its own responsibilities to local nonprofits, rather than actively partnering.

Other nonprofits in the state are working hard to help spread accessible information about the vaccine to Latino and Spanish-speaking communities. Latinx Immigrants of Iowa is one of them. They regularly host vaccine clinics and create and share videos like this one to continue getting the word out about COVID-19 vaccines.

Calzada has an idea of how the state can really make an impact on Latino communities now and into the future. They’re called promotores de salud. Health promoters from the state who work with local communities.

“It's like doing a campaign, you know? Going home by home, knocking on the doors, you know, with the promotores and tell them: ‘Have you gotten your vaccine, yet? Okay, let's do it now.’ And that will be great you know, but you need an army," Calzada explained.

He has lived in California where he said this idea is already implemented across communities.

"The whole concept of creating the community health worker, we don't have that in the state of Iowa. I think that there will be a great solution to this problem," he said.

Now, Calzada said he’s starting to see ideas similar to his pop up around the state. He said maybe taking those steps will better prepare Iowans for health concerns in the future.

To schedule a visit with the UIHC Post-COVID-19 Clinic:

Call 1-319-384-8442 during normal business hours (Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.). Ask to be seen in the Post-COVID-19 Clinic.