The house Curtis White is renovating on Forest Ave. in Des Moines has been torn down to the studs. The siding has been stripped on the outside. Inside, a person can walk through the walls.

For White, it’s a blank canvas. He walks through the gutted main floor with his daughter, Jasmine Brooks, and a realtor who are asking how he plans to create more space in the kitchen.

“Remember, that wall’s gonna be gone,” White said.

White got into business buying and rehabbing homes and apartments more than 20 years ago after a contractor took his mom’s money without doing the work. With some help, he did the job himself and decided he wanted to go into real estate, but he ran into a common problem for Black business owners — he didn’t have good enough credit to rely on a bank for financing.

“First of all, being a minority, you learn to think differently anyway,” White said. “You automatically know those doors are closed to you so you’re gonna have to figure out another way.”

White works with banks now, but he had to work around them to get his business started. He found individual investors to finance his projects. He drew on connections he had from going to high school and playing football at Dowling Catholic.

A lot of businesses stall, he said, because they never get that first investment and he thinks banks could do more for minority business people if they looked past how they score on paper.

“Talk to a guy, go see his work, see what they produce and then make an investment on them,” White said. “We’re figuring out a way to get (financing), but it would be nice — it would be so nice — to have an outside the box type of thinker in each bank to say minorities don’t always have it to do it the way that they do it, but we still can do it.”

Nationally, African Americans make up about 13 percent of the population but only about 2 percent of small businesses are Black-owned.

Racial disparities in business ownership and financing start with a broken relationship between banks and the Black community. Advocates say fixing it will take a new focus on financial literacy and a change in how banks decide who to do business with.Banked versus unbanked

When a business has a working relationship with a bank, it’s easier to borrow money to help grow and hire more workers, said Deidre DeJear, a board member with The Director’s Council, an association of Black community leaders in Des Moines that is working to address racial disparities in Polk County including in housing, education and in business.

“That relationship with the financial institution is, I think, the cornerstone of doing business and it's something that these business owners can't avoid if they want to grow,” DeJear said. “It’s just entirely necessary.”

But, she said, there is a disconnect between banks and Black business owners and you can start to see it by looking at who has a personal bank account and who doesn’t.

An estimated 5 percent of Polk County residents are unbanked, which means they have no personal savings or checking account. That number is about 20 percent for black residents, according to Prosperity Now, a nonprofit that advocates for racial economic equity. Many more are underbanked, which indicates that they use basic services but don’t access credit through their bank.

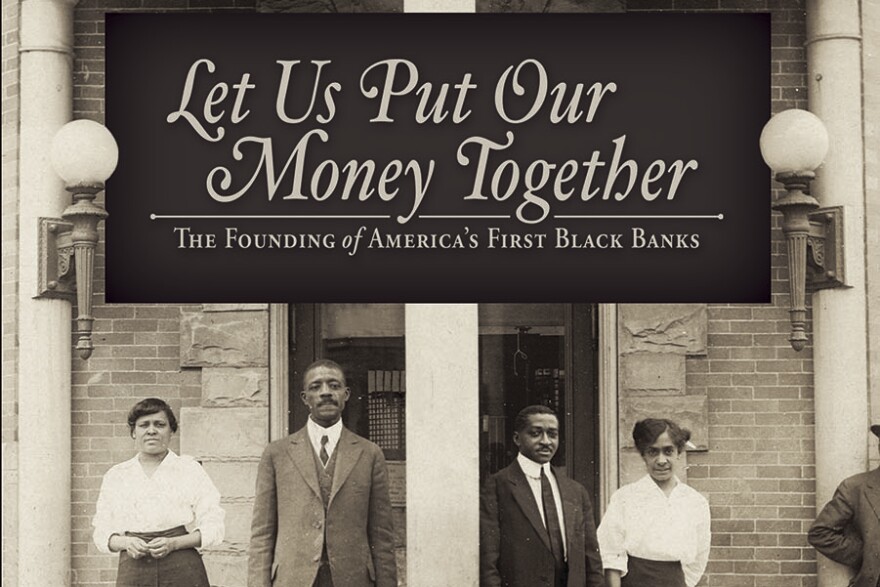

Part of the challenge is that some African Americans don’t trust banks. DeJear looks back to the late 1800s when a bank created to hold the savings of Black Civil War soldiers and freed slaves was driven to collapse by its white trustees. According to a history of the nation's first Black banks, the Freedman’s Bank closed in 1874 owing more than $3 million in lost deposits to more than to 61,000 people.

DeJear said that lost confidence was never fully restored and there is still a legacy of distrust toward the financial establishment.

“You’ve got shoebox savers and mattress savers who were raised to think that you don’t trust financial institutions,” DeJear said. “I definitely think there's some serious history that undergirds our relationships with financial institutions that hasn't been resolved. We have not interrupted the system long enough to make adjustments.”

Unbanked numbers matter, DeJear said, because it follows that many Black business people have no business bank accounts, and the consequences of that played out this year when Congress made forgivable loans available to small businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program.

Banks worked with existing customers first to apply for the pandemic support funding. Many Black and minority businesses were left out “because they lacked something basic and essential, and that’s a relationship with a financial institution — a bank account in their business name,” DeJear said.

In its report on Polk County, The Director’s Council was able to identify only 23 Black-owned businesses county-wide, but later learned that was an undercount. DeJear said many minority and Black-owned businesses are not present on official listings from the Iowa Secretary of State and others because they’re unregistered.

She said the group is encouraging business people to go through those official steps because, like the PPP, it can impact eligibility for state and federal grants, contracts and loan programs.

“We don't want to force them to do something, but what we can do is provide them the information and help coach them through achieving what goals they want to achieve, and a lot of times that's doing something so simple as filing with the Secretary of State, getting an (Employer Identification Number), and getting a bank account in your business name rather than having your business tied to your personal account,” DeJear said.

There has been a run of new Black-owned businesses in 2020, DeJear said, but it’s a trend she’s noticed before, during the Great Recession. She suspects it’s driven by depressed wages and a lack of job opportunities due to the pandemic and not just entrepreneurship.

Some people are going into business as a sort of last resort, she said, because they can’t find a job with wages that allows them to make ends meet.Access restricted

Even people who want to open a basic bank account to support them or their business are sometimes denied access. Many banks use consumer reporting systems such as ChexSystems to screen account applications. According to Chi Chi Wu, an attorney with the nonprofit National Consumer Law Center, the databases report past incidents of overdrawn accounts and suspected fraud.

“Talk to a guy, go see his work, see what they produce and then make an investment on them.” - Curtis White on how banks can work more closely with minority business owners

“These databases are kind of like a credit report except the information in them is predominantly negative,” Wu said. “So unlike a credit report, where if you're paying on time monthly that'll show up, information on this database only shows up if there's been a problem.”

The databases can be unreliable, Wu said. They can raise suspicion of fraud even for people who are victims of identity theft and the definitions banks use for other labels such as “account abuse” are inconsistent. People of color, Wu said, are more likely to be screened out because of negative marks on their history, such as overdraft charges.

“There is a growing recognition that excluding consumers from the banking system is not good either for the consumers or economically in general,” Wu said. “You need a bank account to be able to do so many things, and it would be extremely hard for an entrepreneur to start a business without a bank account.”

Wu said that although banks commonly use screening systems to approve new accounts, some are also providing more options for people who might be flagged for their bank history to still have access to basic services.

“It used to be that (those applicants) might find it almost impossible to open a bank account,” Wu said. “There are now efforts around the county to try to provide safe bank accounts or second chance accounts for consumers.”

Wu said second chance accounts often come with a fee, but can help restore basic bank access.

Five bank companies operating in Iowa, including Bank of America and Northwest Bank, offer Bank On certified accounts. For a monthly fee, the accounts provide most of the usual checking account services like a debit card and online bill pay, but cannot charge overdraft fees.

DeJear said financial institutions should work harder to create access, not restrict it.

“I think that it's critical for us to think about how we strengthen the system and how we create opportunities for those folks who don't have the conventional credentials to get banked,” Deidre DeJear said. “They’re leaving people out.”

Jayne Armstrong, director of the Iowa office of the U.S. Small Business Administration said the issue of financial inclusion is getting new attention. She said more counseling programs are starting up around the state to help people open a bank account or a business.

“We just need to do a better job of building those relationships so that everybody has equal opportunity to start up a business and to grow it all across the state,” Armstrong said. “And part of that, too, I think we need more diversity in a lot of our lending institutions. Whether it’s women, women of color or Black loan officers we need more diversity so that the lending institutions really reflect the community.”

Organizations such as the Financial Empowerment Center and the Iowa Center for Economic Success provide personal and business financial coaching. Kameron Middlebrooks, who coordinates a Master Business Bootcamp for small businesses and nonprofits through Iowa State University Extension, says having a coaching relationship can help create borrowing opportunities that would otherwise be unavailable.

“What I have noticed is the banks that see that a business owner does have a coach they're working with, over time it's easier for them to build that relationship.” Middlebrooks said. “Because this person is working with somebody to ensure their success, and you're not just leaving them out there on their own.”Closing the gap

On Forest Avenue, Curtis White says Black business owners can have better relationships with banks and his daughter, Jasmine Brooks, is proof. Three years ago Brooks started her own version of the family business, Brooks Homes, building new houses instead of fixing up old ones.

Brooks said she takes pride in the fact that she is a Black woman breaking into the housing industry. But, she said, it’s clear that some who work in housing and construction don’t expect someone who looks like her to be in charge.

On a recent job, she went to the building site to answer a contractor’s questions. “I said, ‘Sure, I’m coming right over.’ Throw my coat on, run over and I say, ‘Okay so we need this and we need that.’ And they’re looking at me and they say, ‘Is the builder gonna be here?’ I just looked around and I was in disbelief, and I said, ‘I am the builder.’”

Brooks said she learned the ropes of the real estate business by watching her dad. He taught her how to manage money and how to get a loan. They’re always swapping books about business and leadership.

“I can take the lessons he taught me and the things that I’ve seen him do and apply it in a different way,” Brooks said. “His ceiling is my floor.”

It was a tip from her dad that helped Brooks get her first bank loan for the business. Three banks had already turned her down or offered the bare minimum she needed to start a new building project. He recommended a fourth bank that provided full funding, something Brooks’ father didn’t consider an option early in his own career.

“From my Dad’s generation to me, when I need something financed I go to a bank,” Brooks said. “In one generation it can be changed for minority families. In one.”

Brooks said she had something that too many Black business people don’t have — someone to hold the door open so she could work within the system instead of having to work around it.

Iowa Targeted Small Business Program

A directory of businesses operated by women, veterans, minorities and persons with disabilities

Businesses certified through the Iowa Targeted Small Business program are listed in a statewide directory to provide exposure to potential clients and contractors. They also have early access to bid on state contracts and can apply for financing through a dedicated loan fund.

- Email: tsbcert@iowaeda.com

- Phone: 515-348-6159

Iowa Small Business Administration

Operates multiple business development and mentorship programs

The Iowa SBA operates loan guarantee and disaster relief programs. It supports business planning assistance through 15 Small Business Development Centers across the state as well as throught volunteer mentoring at local SCORE chapters.

- Phone: 515-284-4422

- Learn more: https://www.score.org/

Financial Empowerment Center

Personal and business financial counseling

One-on-one business coaching through the Financial Empowerment Center provides assistance with management, marketing, registering a business and creating a business plan.

- Phone: 515-697-1450

- Learn more: https://www.empowermoney.org/business

Iowa Center for Economic Success

Counseling, classes and other services for entrepreneurs

The center provides classes, workshops and counseling for small businesses. It also operates the Women’s Business Center through the Iowa SBA and provides lending through the Iowa Economic Development Authority.

- Email: info@theiowacenter.org

- Phone: 515-283-0940

- Learn more: https://theiowacenter.org/

Iowa State University Extension and Outreach

Resources for small businesses, nonprofits and local governments

Programs from ISU Extension Community and Economic Development include Master Business Bootcamp, a six-week coaching and mentoring course for businesses and nonprofits.

- Email: kameronm@iastate.edu

- Phone: 515-231-5055

Bank On

Certifies affordable second chance bank accounts

Bank On is a program of the Cities for Financial Empowerment Fund that certifies second chance checking accounts. Banks may offer their own versions of the accounts but certified accounts must meet national standards for affordable access.

- Email: bankon@cfefund.org

- Learn more: https://joinbankon.org/coalitionmap/