“The people who live in ghettos who have been bypassed by our system because of their color but to a degree bypassed because of their poverty.”

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established the 11-person National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner Commission. The congressional commission was to identify origins of racial tensions after a summer of riots around the country. The conclusion of the report was that a combination of racism, economic disadvantages for people of color, failed social service programs, police brutality and more led to intolerable conditions in Black neighborhoods. The report became a bestseller, and its recommendations were largely ignored.

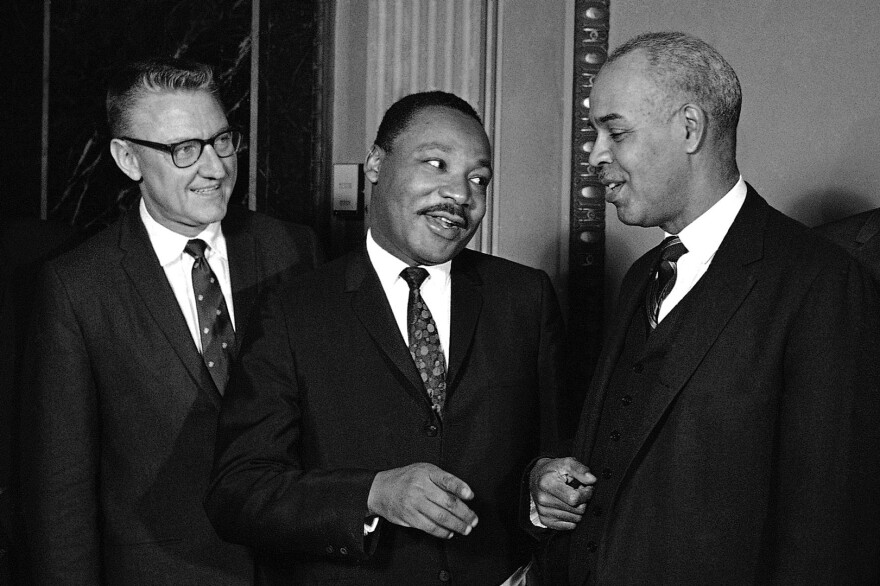

California Congressman James Corman served on the commission. On the fifth episode of From the Archives, Corman presents the findings of the report at Grinnell College during a memorial symposium honoring the late civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

Adrien Wing is the associate dean for international and comparative law programs and the Bessie Dutton Murray Distinguished Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Iowa College of Law. She joined this episode to offer context for Corman’s remarks, speak about the Kerner Commission’s report, and she shared some of her own memories from that long, hot summer.

From the Archives was made possible through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The transcript was produced using AI transcription software and edited by an IPR producer, and it may contain errors. Please listen to the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Thank you very much President Leggett. I'm honored to be here to speak to the faculty and students of the oldest 4-year college west of the Mississippi River. I myself am a product of what was once the finest University, free east or west of the Mississippi, but then we elected Governor Reagan and he changed all that.

I am indeed honored to be here. Most honored because of the occasion which brings you together, because I will mention to you in my closing remarks, I did have the great opportunity to have shared some things with Martin Luther King Jr. But I have to tell you that it's very interesting to serve as a member of the House. I had not been aware of it until some 48 hours ago, but Grinnell has its own representative there, as you know, by way of Pennsylvania, Tom Railsback serves with me on the House Judiciary Committee. And he asked me to extend his good wishes, particularly to any of you who do or may in the future vote in his congressional district.

In addition to serving on the House Judiciary Committee, I had two extra assignments during the this term. You may recall that in 1966, the folks in Harlem thought they had elected themselves a congressman, but the Congress didn't know for sure whether that was right or not. And so we did not see Adam Clayton Powell, at the beginning of the, of the 90th Congress. Instead, the House instructed the speaker to appoint a nine member committee to investigate Mr. Powell and to decide whether or not he should be a member of the United States House of Representatives. And I was one of the nine selected by the speaker to make that inquiry. It was an interesting group. We were chaired by the Dean of the House, Emmanuel Seller. And we had five Democrats and four Republicans, and we sort of ran the gamut from very liberal to very conservative on both sides. It was an interesting experience, because we thought we ought to look carefully at what Adam had been doing for, for the last 2 or 3 years to cause so much indignation. And we discovered that he'd been active. For one thing, shortly after he had married a very attractive young lady. He went off to the French Riviera with two of his secretaries and stayed a month and came home, and none of them was angry with him. And we told him if he would tell us how he did that, that we'd drop all the charges. Well, Adam was not cooperative with us at all. And we got to saying some harsh things about him in the committee. And the youngest member is Andy Jacobs, from your neighboring state of Indiana. And Andy, got a little bit upset with what harsh things were saying about Adam and finally he said, Mr. Seller, I think we should follow the admonition of the old Indian chief: 'Never judge a man until you've walked 8 days in his moccasins.' Mr. Seller said, 'Oh, Andy, do you think you could walk 8 days in his moccasins?' And he said,' Well, Mr. Chairman, I didn't say 8 consecutive days.'

I mentioned the power committee, because the fundamental issue in that committee was somewhat the same as the Kerner Commission. But the nine of us worked very hard to bring back to the House a unanimous recommendation about what ought to be done in the power case. Seriously, we felt the issue was a clear-cut constitutional matter. Powell was qualified to serve and he had been elected without question by the people in this district. And we thought that was all that ought to be looked into. We had great difficulty arriving at a unanimous recommendation as to what ought to be done about it, because in truth he had, he had misconducted himself, and we thought that the suggested punishment was appropriate. And we all nine agreed to it. And we took it back to the floor of the House. And it was rejected out of hand. And the House did not seat Adam Clayton Powell, and I think they did violence to the Constitution. And they harmed the House in that decision. I think there's no question but that Adam Powell would be a member of the House today, if it were not for his color. That makes the problem doubly bad.

I mention it because the 11 of us who served in the President's Commission on Civil Disorders, worked very hard too to come up with a unanimous recommendation. It was difficult. If you read the foreword, you'll understand that we did not all agree precisely on every step that we thought ought to be taken to meet America's problems. But we were unanimous in our conclusions as to what the fundamental problems were. That were evidenced by the summer disorders of '67. And I hope, sincerely, that the American people will not reject that unanimous recommendation. I plead with you and I take it that you are concerned, do what you can to see that America does not repeat its history of a century ago when it looked as if we were on the verge of some substantial improvements in the quality of our institutions and our way of life. But all of that went by the board with the rise of Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow and equal but separate. We just mustn't let that happen again.

You'll note that the membership on the commission was rather diverse. The only thing I can indicate to you as to why the two members were picked from the House, it was congressman McCulloch, from Ohio and myself, and we both have been very active in trying to hammer out civil rights legislation over the past six or seven years. But there was an industrialist who has been a very successful one, a labor leader who had fought his way up from the ranks of labor to become the head of one of our most significant unions. I think, in many quarters, one of the most respected civil rights leaders over the long haul, and in the Negro community, two senators representing different areas of the country and different economic backgrounds. A very articulate mayor from the big city, a governor from Illinois, and a police chief from Atlanta, who I suppose turned out to be the most surprising member of the Commission. And a very active civic leader and leader in women's affairs from Kentucky. I guess that's all of us. The President called us together and told us that he wanted us to find out what happened in America in the summer of '67. And why it happened, and what ought to be done about it. He admonished us to attempt to wipe our minds clear of any preconceived notions, to give a fresh approach to the problem, and not to be bound by any former conclusions. I would tell you that the President did not, in any way, during the seven months of our writing that report, in any way attempt to influence our decisions or our recommendations. From that point forward, he gave us an ample budget, a good staff, instructions to every administrative agency of the federal government to cooperate with us in any way we saw fit. And then he left us to our duties.

It was an interesting experience. I can't say that I learned very much more about America's problems that I learned as a result of our hearings on civil rights bills in 63, and 65, and 66. Because the congressional committee in areas such as that gets a pretty close look at some of the, some of the troubles in our land. But I did have the advantage of talking with lots of people and seeing the views of my fellow Commissioners crystallize and shift as we moved down that road. I believe we had a sound approach at finding out what happened.

We had everyone from the local police departments to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. To help us piece things together. We used our own investigating teams who moved into ghetto areas and lived there for six or seven or eight weeks. We had hearings in Washington, we heard testimony from a wide range of people. And we went out into the ghetto areas ourselves for three or four days at a time and talk with people on the street, people in the police stations, people in tenement houses.

We concluded that what had happened was not nearly so serious as we had thought and probably the American people had thought as a result of what they saw on television and read during the course of the summer disorders. It just wasn't as big as it looked at the time. And I don't think that that was an intentional misreporting. But rather just that disasters such as that condensed together on a television screen or in a news story, get exaggerated. And those who concluded that this great nation was on the verge of revolution, or rebellion, or that we were about to be torn apart were, I think, wrong.

To say that there were only 80 deaths isn't to minimize the tragedy of any American being killed in American street because of a civil disorder. And yet one would have been led to believe by some of the reports at the time that there was in truth armed warfare in our cities. Now it had approached that a little bit in Detroit, it really didn't get that bad at all any place. But if the what happened, didn't look as bad as we thought it was going to the why looked much worse. And it was the why that we suggested that has gotten to the commission the most publicity, for good or for bad. We said it was white racism.

Now, that's a harsh term. We talked about it a long time in the commission before we decided to use it. Some of us, and I was among them, had apprehension, that we might lose the the favorable attention of our audience, if we use that term. And yet, if it makes people think about what kind of an America we have, what kind of institutions we have created for ourselves, and how deep and pervasive they are, then we will have selected the right term.

One of the questions the President asked us was whether or not there was conspiracy, that played a part in the disorders. This is a theory that is very comforting for white suburbia. As a matter of fact, I suspect for a long time in this country, we have tried to pin our problems, on conspiracies of some form, and preferably communistic conspiracies, if we can find a handle. That was one of the things we devoted a substantial part of our investigative work to.

We came up with the conclusion that neither local nor national nor international conspiracies played any part in the disorders that were visible on this land in the summer of '67. And that was corroborated by every law enforcement agency with whom we had any dealings and was certainly corroborated by our own investigating staff. Having said that, I ought to add that we point out in the report, that there have been efforts to conspire to cause disorders, and they have been frustrated. There will be efforts in the future, there will be efforts on the part of communists, I suppose, to take advantage of the disturbances to attempt to infiltrate belligerent Black nationalist movements. And one cannot say that because it didn't happen in '67, that will never happen. But it would be the worst kind of dishonesty to ourselves to say that the disorders in '67 were the result of conspiracy, so that we could hang the blame on somebody other than our own institutions in our own society and in truth to ourselves.

We saw that a substantial part of America has moved in the past two generations, from rural areas and small towns to big cities. And then as they moved into big cities, they segregated themselves, sometimes by law, more often by practice, but always with a system that forced the Negro into the older, more dilapidated part of the city. In overcrowded conditions, where public services and particularly public education is criminally poor. Where jobs are not available and have surrounded those core cities with a white suburbia that is afluent beyond anything that was imagined when I was an undergraduate, fewer years ago than you might believe, less than 30. But we seem to be headed down that road at a frightening rate, and not much being done to stop the trend. And as the report points out, if we continue down that road, we will have a seething mass of angry, frustrated people, surrounded by an affluent mass of selfish, fearful people, who will tend to come more and more in conflict with each other, to the point that we threaten ourselves with some form of police state to maintain any kind of domestic peace.

And we turned our attention to what ought to be done about it. The first thing that, it seems to me and I don't speak for the whole commission in this respect, it seems to me that we must first effectively remove racial barriers at any point in a man's existence, if he has let in and or kept out because of his color, then we just haven't perfected our society. And so I've long been an ardent advocate of such legislation as that which we just passed the federal, rather comprehensive and I think, enforceable open housing law. I've supported all of the civil rights legislation that they've written into Congress since I've been there. And I think there are still some areas in which we need to move, but we're doing quite well.

But that's only a half of the problem, and perhaps the lesser half really. If you're going to tear down the barriers, then simultaneously you have to give the people who have been stopped up to this point, the economic ability to move into that area that you now say he can go into. What good would it do a Negro in Pacoima in my district, who makes $3,000 a year, to now tell him that he can move over to Van Nuys with me, where houses cost $30,000 a year? That open housing law means nothing to him.

And so along with the our efforts at breaking down these racial barriers, we suggested that we need to give special attention to the educational and economic problems. The people who live in ghettos who have been literally bypassed by our system, in large part bypassed because of their color, but to a degree bypaseds just because of their poverty. Those things are not --That's that's one thing you really can't segregate is the poverty and the color. Because it is the barriers we've put up because of color that have led so substantially to the poverty itself.

We suggested that one of the first things we must turn our attention to is employment, meaningful employment, for the masses of young people who live in ghetto areas, who have really had no reason to hope for a meaningful job if they are to base their hope on the generation ahead of them. A great number of young people who live in ghetto areas, live in families where the mother is a domestic servant, the cleaning lady. The father, if he is about at all, has great difficulty getting any kind of employment. He has little reason to stay with his family if he has a sense of pride and dignity, which I suppose all men have, because he must go through the indignity of seeing his wife support the family. The children have little in the way of parental supervision. They are, particularly in the big cities, they become the product of the street, their intelligence, their brightness, turns to ways to make it that are available to them. And if they're not the classical Puritan ways that you and I were probably taught ought to be followed. They aren't going to be satisfied, nor are we going to meet our responsibility, if we give them jobs washing cars, or shining shoes, or cleaning toilets or as janitors, or out in the forest, digging ditches and chopping down trees. Rather, they're going to have to be given the opportunity to acquire some kind of skill that is marketable. And then be able to move into a productive society, where they know that if they apply their skill, they work hard, they have the same advantage of advancement as anybody else.

Now that's simply stated, extremely difficult to accomplish. Not because a 21-year-old Negro boy is any a different from a 20 year old white boy. But rather because of what has happened to him in the first 20 years of his life. Many boys reach that age, even with high school diplomas, who are barely literate, because the system works that way. Many of them reach that age without ever having an opportunity to know the value of self discipline. Because they don't live in a society where self discipline is of any meaning. It's going to take a lot of effort and special attention, and a lot of public expenditure to meet that part of the problem.

Now there were lots of reasons to be discouraged, as a result of the investigations. As I say, the the racial discrimination, which we felt was at the root of it is difficult, from two points of view, really, for the people who really have the hatred in their heart -- and I suspect they're not many of them -- they don't convert easily. They're -- some of them, I guess, not really born with it, but they have acquired at an early age and they're going to take it to the grave. They really convinced that an integrated America would be an evil. But the other problem is the people who just have refused to think about that part of America. I think the herblock cartoon the day after the commission report was was issued was as good as any analysis. If you remember, there was a man sitting in his penthouse on the top of a very beautiful apartment house with a cocktail in his hand and his sunglasses on sunning himself, and over here was the sweltering slum. And he said, what do they mean, it's my fault? I have never even been in a slum. That's true he never had. But he was a preserver of the institutions, which have in turn preserved the slums.

I've had occasion to talk with lots of different people since the '63 hearings about America and what they'd like to see changed. I guess the lady at the bottom of the ladder was a plantation worker just outside of Yazoo, Mississippi. We couldn't get permission to travel when we had the civil rights hearings, and so I just got in my car and headed south and then west, I went as far as Vicksburg, I just stopped and talked with people, to try to get some feeling of what conditions were and what kind of legislation might be helpful to change it. You may remember that that was the the act that that brought about the public accommodations section where you, you couldn't have segregated public accommodations any longer. That was really a big step forward for its time. But out on this little cabin, on the plantation, a lady who had seven children. The family made $1,500 a year, and the overseer told me that his employer was one of the best because families could really make it there. A family of man and woman and five children of age to work could easily earn $1,500 a year, and their quarters were free. Now the quarters for these nine people, she had seven children, was a two room shanty. And I asked her if she could change one thing what she would change. She said, Well, she'd like for all of her children to be high school graduates, she really had no hope of that. Because already those who were over 12, had left school and gone to them to the field, chopped cotton.

I asked a negro school teacher in Jackson. In those days, it was illegal for a negro to teach in a white school or for a white teacher to teach in a negro school. Segregation didn't go just to the students. it went for the faculty also, that wasn't many years ago. I thought maybe he'd tell me he liked to vote or some such exciting thing. He told me he'd like to be able to take his wife to see the the ballgames at the public Stadium, Jackson, Mississippi, because he had been an athlete in the Negro League and very interested in football. But because they were black, they couldn't see public games in the stadium. During our commission, I asked, among other people, Martin Luther King, Jr. If he could change one thing, what he would change? You probably all know the answer. He said he would change the attitudes of the American people. And I think that's what our commission tried to say. That's what we must do. We must change our white attitudes of complacency. And to what degree it's necessary, the Black attitudes of acceptance of a system that is in truth intolerable and completely inconsistent with our basic principles in this country.

And among other people, we went to talk to where some of the the angry young negros and they got us a roomful of them. And I'll tell you, they were angry. It's the first time that I've ever been criticized for anything other than my political party. I was called a honkey and all kinds of things indicating that, because of my color, these boys hated me. And you could see it in their eyes. There was no talking with them, or reasoning with them about civil rights legislation or anything else. And they were very bright young men. And I was terribly depressed. I thought, if they are the future, if they are that irretrievably angry, then we're in for hard times. As I was leaving the hotel, to go back to Washington, I wanted to make a purchase. And I saw all these young fellows standing at the front door just finished our, our session. And I asked him, if he could direct me to where I could buy a stereo tape. And he started explaining to me how to get there. And it was a circuitous route. So he said, Well, I'll take you there. And so he walked eight blocks there and eight blocks back to see that I could make my purchase without getting lost. And on that walk, we talked about what it's like to be a congressman and what I had done when I was his age, and where he went to school and what his family life was like. When we got back to the hotel, he shook my hand. He invited me to come to his home if I was ever back in Detroit, and promised that when he got to Washington, he'd come to see me and we parted his friends. And that was encouraging. Another encouraging incident was in Tampa, you may remember that Tampa had what looked like a full blown riot, and it was cut off in its second day and ended by some white hats.

The white hats were a group of young Negro man who were given White Helmets by the police chief and they went in and physically stopped the riot. And we went down to see how they had accomplished this. It turned out that Tampa was blessed with a very active and effective Human Relations Commission. They had as their Executive Director a man named Hamilton, the former Army major and a very, very competent man. And he knew who were the leaders in the ghetto area. And when the riot started on its second day, when it became apparent there was going to be full blown, He asked the police chief for permission to go in and get the Negro leaders, bring them out and talk with them before they set in the police in the troops. The chief agreed, he brought up five young man who in turn, went back in and got their gangs and got themselves the white hats in a relatively short period of time, it was all over. And I had the privilege of talking with those five young man. They were all school dropouts, I don't think any of them had gotten as far as high school. Everyone had been in jail, and one had been in prison. They were between 17 and 21 years of age. They had a quality that I suppose Marine Corps recruiting sergeants look for, you could see by their physical appearance and their personality, they were born leaders. They were a young man of reliability. And they told us what had happened. One young man said, when he left his home that night, he was intent on burning Tampa down, they were going to burn down the Negro section, they're going to move over and burn down the white section, business district. But after he talked with Hamilton, he decided to do his best to stop the riots. And he succeeded in that. And I said, 'What made you change your mind?' He thought a long time. And finally he said, 'Well, Congressman, that's the first time anybody ever gave me anything important to do, and I wasn't going to fail.' Now, there are a lot of great capable young man who are in a real sense, the the wealth of this nation. Many of them live in those ghetto areas. We need to give them something important to do we need to do something important ourselves. And that's to tear down the last racial barrier in this country, to give to all Americans, whatever quantity of education and training, they have the ability and the gumption to acquire and let them all move into society on an equal basis. I'm not sure we'll love do it in our lifetime or even your lifetime.

But there are reasons to be optimistic. I suppose the greatest reason of all as the objective is so desirable. This country has been very kind to most of us needs to be kind to all of us, and I think that it can I commend you, in large part for your recognition of a truly great American, Martin Luther King. I had the privilege of listening to him testify in 1963. That was my first experience with him. I watched his contribution to that very significant march of August or of March, August of 1963. I watched him before our commission. I participated in the procession that honored him in Atlanta two weeks ago, Sunday. He was a great force in this country. And with tributes such as you pay him now that force will not pass from the scene. But it was a great loss. And this whole nation is poorer because of it.

I don't know if you want to take a break. Are you likely just to go ahead and try to respond to some questions I'd be glad to do whatever you say.

Thank you all very much I was going to say, I do not often get to speak from a pulpit. But this is the only time in my entire life, and I am a fairly methodical Methodist, I have seen a group this size in the sanctuary anytime other than the 11 o'clock services at Easter time. I'll be glad to respond to questions, but first must qualify myself appropriately. I recently married and my father-in-law was the only one not able to attend the ceremonies. And at my first opportunity, I went up to Wisconsin to meet him. And this was the last Sunday in March. And my bride said, Papa, this is my husband, the Congressman, he knows all about what goes on down in Washington. The old john looked over his glasses, and he says, who's going to be elected president next November? I said Lyndon Baines Johnson...Six hours later on television... I hope that my answers are even more accurate to your questions. Are there any? Yes?

That first of all, let me ask, could those of you in the back of the room or up in the balcony there? Could you hear the question? All right, and I'll repeat them all. The question was, do I think integration should be an immediate objective? Or must we first have some economic aid? I tell you, I think those things must go hand in hand, I don't think that that integration will be truly meaningful for a great number of Negroes unless they have the the financial ability to move into society. But I do not think that there is any justification for perpetuating racial segregation in any form at all.

...I think that right now, we must decide that we're going to tear down every barrier that the Negro faces, and I am very much opposed to the theory of gilding the ghetto, of making it a nice place to live of letting the Negroes own their own businesses in their own industry and their own banks and keep them all down there where they won't bother us. I think that is just a step in the wrong direction. I think that, first of all, for every American, and there are a tremendous number of poor white Americans, we must be concerned about their capacity to have a a reasonable living standard. But that's only a half of the problem. They must have the right to move about in our society, under the same rules that the rest of us do. That's going to be difficult, but it's already started. And I think we're pushed as best we can. maybe I didn't quite respond to your question.

...I don't have any quarrel with negros owning their own businesses. I have a quarrel with a setting up institutions which make it possible for Negroes to own Negro businesses, white people to own white businesses as a method of perpetuating the separation. I you know, it's dandy with me if a negro owns a business, I hope it's investors in the white community...Yes, sir.

...Well, I reckon there'll always be rich people and poor people, a whole lot of us in between those two poles. I just reading in the morning newspaper that they've listed the 160 Americans who own more than $150 million. And I feel sort of poverty stricken when I think of my bills next month, I think of that. But we were looking at what caused the riots. We talked a lot about poverty. But it wasn't just poor people who were rioting. It was people who have been kept poor because of their color. Now, there are obviously lots of people, Negro, and White, who have very limited capabilities. You know, not every baby is born with an IQ of 130. And there are all kinds of physical and mental and emotional problems that will keep people in the lower part of the economic bracket. But you just can't say that the color of his skin is going to be one of those things. Because that black skin may cover a highly intelligent, highly motivated, young man or woman who just isn't going to be content to do menial tasks all of their life, knowing that they have much greater capability. But they're relegated to that because of their color.

Now, I have a training center in my district. We call it a vocational training center, I saw a young fellow who brought a substantial expense to the United States government was learning to be a dishwasher. It turns out that washing dishes isn't exactly like we used to think of it but to be a dishwasher in a big restaurant, you got to learn to operate some mechanical things. This boy had an IQ of 70, he was a white boy. And 70 doesn't give you a lot of range. There are not too many things he could-- he'd have trouble as a freshman in Grinnell, I'll tell you, but we don't even know how he passed the selection for Dewey. Anyway, he was learning to be a dishwasher. He got as much satisfaction out of that learning process. As I got going through law school, he was he was acquiring a profession. It took a lot of special attention, not any more than it took to make me a lawyer, but it took a lot of attention for him. And nobody ever thought much about people like him before we got into this area, this kind of highly specialized, concentrated education. Anyway, the last time I saw him, he was making $125 a week, it was a very menial task. If I had that job and figured out how to do it the rest of my life, you know, I'd be ready to revolt. But he liked it, it sort of was his capacity. It took a little effort, a lot of effort to give him that. I think that's what we have to do for for everybody. But we've just got to somehow make these things available on their own capacity and initiative and not let it be denied them because of their color.

Now, I also think that this rather affluent society of ours can put a pretty reasonable living standard at the floor and say nobody is going to sink below bow. There are a lot of people who just physically or mentally do not have the capacity to work too young or too old, or they're too ill, and we shouldn't bypass them. But it does seem to me that the heart of the problem we looked at was the fact that we have kind of eked out this area of poverty. Instead all of you who are Negro, with with some very minor exceptions, are going to be compressed in there. There is a growing Negro middle class, and I think they must become terribly frustrated too. Because even though they'd become more fluent, they still catch the indignities and the and the sarcasm, the other things that plague negros all the time they get them whether they're PhDs or ditch diggers or whatever. They get them in my district. I wouldn't be surprised they might even get them here. Yes, sir.

...Well, I don't know, are you telling me that negros have ethnic identity and whites do not? We all 'live in boxes made of ticky tack' as I remember the ballad, and I think it's a very accurate one. And I must say that some very bright negros have asked, you know, man, why do we want what you got, that's your bag, and we don't want it. But I'm not sure we all want it either. I wouldn't tell you that white suburbia is, is having come to worth at all.

We, we got our burdens to bear. And we need to do better than we have done in the next generation is going to do better than we have done. And having a richer society. Not richer in terms of dollars, but richer in terms of accomplishment. I'm not suggesting that we, we ought to force the Negro into that mode at all, I say that he ought to have access to, to the influence that that we decided to use that way, let him use it however he wishes. But don't tell him that he can't first of all have the influence. Or secondly, if we say, all right, you can have it, but you can't spend it the way I'm spending it, because then you'll be too close to me. Just saying that that's what we ought not to do. And I'm not at all sure that that suburbia is as homogeneous as you would be led to believe I represent a district that is almost entirely suburbs, although we have a handful of Negroes and a handful of Mexicans 82% each by district is about 600,000 people. They are the third best educated congressional district in the nation, the 12th richest. And we have some of the evils of of that suburban life. You imagine.

On the other hand, I think we have some some vitality and some interest in reform and and change that is emerging. That is good. And I think as we move further and further from those days of our economic depression, and really before that there's always been a condition of material want in this country that unsatisfied but now we have the capacity to satisfy everybody's physical wants, that will become less important. You won't be gauged by the make of your automobile or the length of your swimming pool. But you'll be gauged by some other things that are maybe you won't even be concerned about whether you're engaged at all or not. And we all need that kind of reform. But let's don't let's don't keep the Negro just on the theory that he won't like it if he gets here...Yes, sir.

…There were some negros some, some whites who participate in the riots in the ghetto in Detroit is more integrated. And as most places, most places you can almost find the street that divides the poor Negroes in the poor whites. And actually a riot or those, those riots that we were looking at are such disorganized, unexplainable kind of things that, you know, any kid running down the street is going to grab a watch or a television set or whatever. You don't have to have a particular color to get caught up in that sort of thing. But I think again, the difference in the poor Negro in the form of white is, you know, there are some similarities as to why they're there. But the big thing is that the Negro isn't given the access out of that neighborhood living standard, that the white is a tremendous number of white suburbanites came out of the same physical structures as the people who now live in ghettos. But they had an easy way out And then the grow doesn't have that in the same way certainly. And I don't think we can satisfy ourselves with wanting to the handful who make it as being a, you know, conclusion that the others have the same chance because they don't really

…Sir, that it gets to be hard to repeat the questions. That gentleman asked me to comment on the the-- there are three possible ways of getting a equality for the Negro, the one is the way the commission report urges. The other would be power blocks, mostly Negros, but of all white--I mean, of all poor people. And the third is, is, is a aggression. Physical disorder. I, although I don't think your cynicism is is, is completely irrational, I have to tell you that I don't share it. Because I have got absolutely no hope for the other two approaches. And I think we just have to find our way out. I just don't think we can surrender. We've got so much here. And we deny ourselves so much. If we keep up the 10 or 15% of the people who are kept out now.

Now the theory of political and economic powet for people who are in the circumstances of the poor in the Negro, the poor man in the early 30s was the hero in this land, because that was all of us. But the poor man today is not the hero because he's only about the outside 20 or 25% of us.

Outside of the Negro community, the white poor is leaderless because they do not constitute any kind of significant political bloc, any place. And you get past that political bloc, that is the labor union organization, that these folks out here are just disorganized and incapable of anything. And so I don't think that they are a potential power block in themselves. Then, if you move on to the worse approach of some kind of aggressive violence, to coerce change, it seems to me very probable that that is so counterproductive, that it will destroy any possibility to for us to bring about change within our structure. Because the part of the white community are the controlling community that wants that change will just be run over and submerged by people who are fearful and angry.

Tell us little girls were killed by the bombing of the church in Birmingham. And the bill was reported out the next day. I cannot tell you for certain what would have been the outcome of the 68 Civil Rights Act, had it not been for the tragic assassination of King I think perhaps it might have passed, but never with the majority that it did. And so events like that, in a sense, seemed to bring America to her senses. On the other hand, events, such as the rioting in Detroit, leave Detroit with an almost total lack of capacity to move in a direction of real integration and equality. And so No, I just don't think that that that kind of action is the answer. Now, if you in truth had armed rebellion, the impact on the white would be much, much worse than it is now. Actually, the white community as such as suffered almost not at all from the from the civil disorders. But if you really had guerrilla kind of warfare, I think the the, the end outcome would be complete destruction of a significant portion of the Negro community, and we'd never really work our way out in any kind of a solution within the framework of our government.

…Next question.

It's a difficult one to answer. I do not know the reason for the President's response, the Vice President's response was very warm and friendly and supportive. I read the entire speech which he delivered. That speech commended to the commission and its report. He said in it, that the fact that America was moving toward the two separate societies was open to question. That was the only thing that the press pulled out of a 12 page speech. They could have pulled out almost any other sentence. And people would have been saying, well, isn't it nice that the vice president has endorsed the civil disorders commission report? I have neither explanation or excuse for Mr. Cohen, I regret that I'm not a member of the upper -- not at the upper-- the other body, because then I could have gotten to vote concerning his confirmation. (applause)

And I would tell you this. I never envisioned that the Commission was going to make up the mind of the President of the United States, one way or the other. I have tremendous respect for Lyndon Johnson and what he has done in the area of racial relations, the area of social welfare, but I am hopeful that the message of the Commission will be reflected at the ballot box in November of 1968. We're not going to do anything significant between now and November 68. local communities can do some good things but as far as our addressing ourselves to this, this national sickness that we have, as far as are putting into it, the resources that are necessary. The American people are going to decide in November of 68 whether they want to do that or they do not want to do it. I am a little bit apprehensive about the decision they may make. We do the best we can to see they make the right decision. We try to knock commission report to give them some really some fairly sound arguments as to why they ought to do that.