In 2007, I read that the "dispute about classical recording is whether it is dying or dead," but in 2016 it seemed as frisky as kids swarming a playground. So many albums came out that trying to winnow them to a "best-of-the-year" list could make you empathize with an Ivy League admissions officer. Yet the challenge didn't daunt hundreds of critics worldwide, and their choices were fascinating. In recent years I've been aggregating all the lists I could find into a "meta-list," and I wasn't ready to stop just yet, so ... welcome to IPR's 2016 Classical Mega-Meta-List!

This year it aggregates 70 lists with a total of well over 400 contributors. They came from 27 countries, almost twice as many as when the Meta-List project started, because Google Translate made it easy to access sources outside the Anglosphere. Google let me add lists in Danish, Dutch, Estonian, French, German, Japanese, Polish, Romanian, Spanish, and Swedish to dozens in English from as far away as Israel.

Three years are too few to show long-term trends, but they suggest baselines and may even tell us something about the industry in the mid-2010s. Could it be that the mega-meta-lists give a sense of the classical recording “long tail?" That's Chris Anderson's term for our cultural shift "away from a focus on a relatively small number of hits" and "toward a huge number of niches," and it explains how the top-rated TV shows of 2017 get renewed with fewer viewers than "flops" canceled 20 years ago. To be sure, the top fifth of picks won half of the votes, and the top 5% won a third of them - but that's nothing new. What grew in 2016 was the tail. Over 600 new classical releases struck somebody somewhere as belonging on a best-of-year list, and two-thirds of those picks received only one vote. And while no more releases than last year made 10+ lists, more than twice as many more received 4-9 votes. That threshold was reached by 28 CDs last year, but 56 this time. There were so many that I'm reporting them over three posts (Part 2 is here, and part 3 here).

Of course, the longer tail could be an artifact of the wider range of countries surveyed, but that's all right with me, since classical recording is genuinely international in the digital age. And I do feel comfortable saying that an industry that produced 600 best-of-year candidates was not acting moribund. The Cassandras may eventually turn out to be right, but for the last three years the gift horses have been galloping.

For reasons I detail every year, even the most mega meta-list could never tell us which recordings were, in fact, the "best" of the year. [Feel free to skip this list of reasons, but: PR and distribution influence what reaches the ears of critics worldwide; our judgments aren't completely independent; we tend to be more interested in some genres than other equally worthy ones, like band music; and we have unconscious biases that will someday be more apparent than they are now. It will someday feel odd, for example, that almost all of the composers had Y chromosomes.]

But if not all the cream could ever rise to the top of any list of lists, what did rise was grass-fed free-range organic AAA-grade, and without aggregation some of it could have been missed. And who knew that the album that dominated the list would be an indie release of a brand-new work fostered by a rare collaboration of performer and composer? The envelope please:

_______________________________________________

RECORD OF THE YEAR (22 votes)

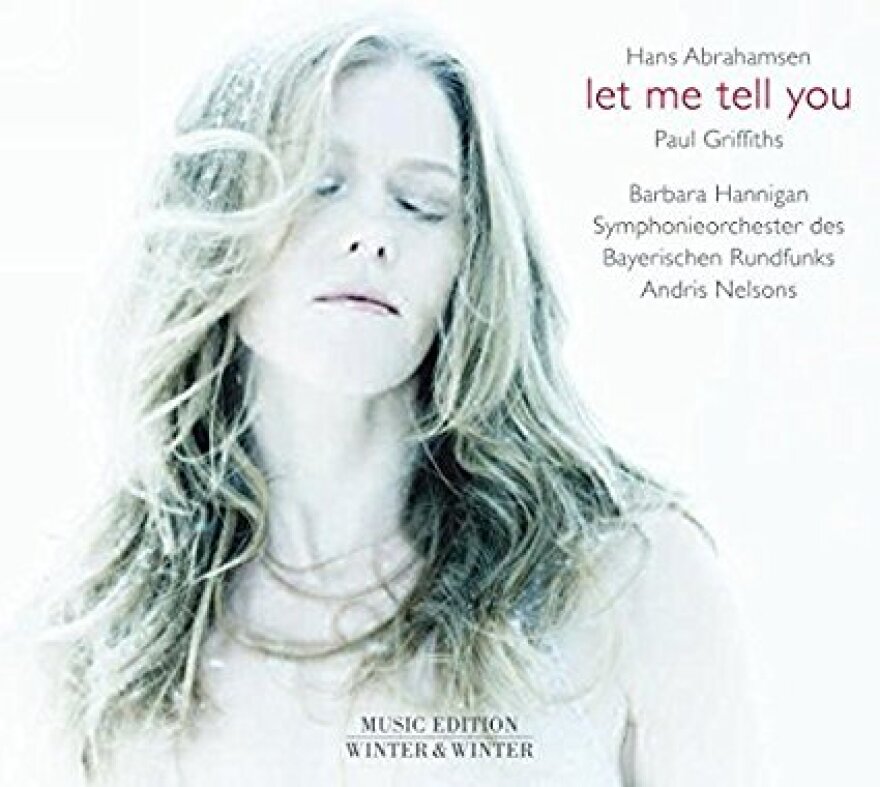

HANS ABRAHAMSEN, Let Me Tell You - Barbara Hannigan, soprano, with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andris Nelsons (Winter and Winter NMC 197)

The release that soared to the top of the list contains a single cycle lasting 33 minutes but feeling more substantial than many operas. When Let Me Tell You had its Boston premiere, says Fresh Air’s Lloyd Schwartz, “at the end, after a full minute of stunned silence, it got one of the most sustained ovations I've ever heard for a new piece.” The reason was partly the gripping performance by soprano Barbara Hannigan, a Canadian who is also a notable composer and conductor. Indeed, she contributed far more than just great performance, but was central to the work's genesis. It was Hannigan who thought of setting a text from a novel by Welshman Paul Griffith, which he wrote with only the 483 words used by Ophelia in Hamlet. And it was Hannigan who decided that the perfect composer for it would be a 63-year-old Dane named Hans Abrahamsen. In turn, just as Handel or Mozart tailored music to specific singers or instrumentalists, Abrahamsen consulted at length with Hannigan about her vocal techniques, ranging from Italian Baroque to modern practices, in order to make full use of them.

The other reason for the ovation was the music that resulted from this collaboration. Let Me Tell You shows that Shakespeare can still inspire musicians to their highest peaks, as he did for the likes of Mendelssohn and Verdi. The cycle's beauty is mesmerizing and sometimes other-worldly, yet always deeply humane. The Ophelia whose inner life it evokes is more complex than the original character, and stronger. Her final words are “I will go on,” and Abrahamsen and Hannigan make us feel them more vividly than we could on our own.

Giving such a voice to the most haunting of victims is no small achievement, but there's more. As Schwartz notes, Let Me Tell You explores not only Ophelia's experience but also "questions of time and memory, nature and human isolation. And what is music if not time, Ophelia sings in Let Me Tell You. Time of now and then tumbled into one another, time turned and loosed, time sweet and harsh. Most important, these haunting works are also extremely moving. Without affection music means nothing...”

The recording deserved affection, and earned it from 22 lists from around the globe. Here’s a youtube of a section from one of Hannigan’s live performances last year:

_______________________________________________________

GOLD (10-20 votes)

Prediction is hard, but disconfirmation is easy. In 2008, a pundit asserted that the “remaining three 'major' labels will be out of the classical business within two years." Instead, in 2016 the major labels gave us most of the classical releases chosen for 10 lists or more. Save for the wintry Let Me Tell You and a Sibelius CD from Minnesota, all were on either Sony or Deutsche Grammophon, a division of Vivendi. Whether you consider that a good thing (the major media conglomerates are seriously into classical again!) or a bad one (conglomerates dominated classical!), it suggests that classical projects made sense to presumably skeptical, tight-fisted Chief Financial Officers. And it's good to note that while the major labels still sometimes push "crossover" projects centered on pretty people performing fluff, what impressed critics was major repertory played by serious interpreters. On to the picks:

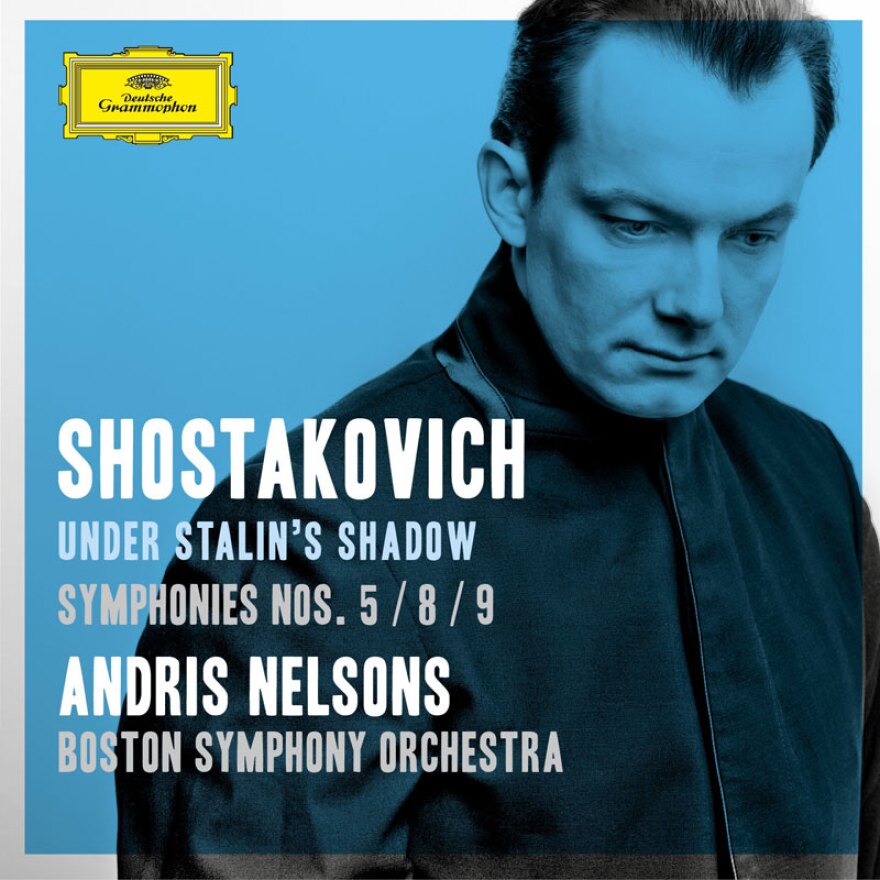

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH: Under Stalin's Shadow - Symphonies 5, 8, and 9; Hamlet incidental music - Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andris Nelsons (Deutsche Grammophon 479 520)

If the name "Andris Nelsons" sounds familiar, perhaps it's because he was the conductor of Let Me Tell You. The 38-year-old Latvian is the new music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus and is continuing in that role with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which appointed him in 2015. With the latter group, he recorded a Hamlet-based set that is much lighter than Let Me Tell You, having been written for a farcical Moscow production of the play. But the composer, Dmitri Shostakovich, was arguably the greatest symphonist of the 20th century, and the main focus of this recording is a set of three of his symphonies that together form a perfect introduction to his range. You should hear this recording even if you already have many other Shostakovich albums in your collection; it is that outstanding.

Shostakovich wrote his Fifth Symphony in 1937 after Pravda denounced his Fourth for its "formalism." To quote NPR, "Fearing arrest, torture and even death, the composer, with sly brilliance and a remarkable spirit, found a way to compose music which appeared to adhere to Stalin's directives while subtly weaving a deeper and sardonic musical truth." Then, at the depths of the war in 1943, Shostakovich wrote the overtly dark Eighth, which, to quote Susan Scheid, was "banned in 1948 by decree of the Party’s Central Committee following a series of hearings on charges brought against 'deviant artists'.” That ban also applied to 1945's more comical Ninth, even though earlier it had been nominated for the "Stalin Prize," which, of course, it did not win.

Nelsons knows from experience about making music under the totalitarian boot. He was 12 when the USSR collapsed, freeing his native Latvia and allowing his grandfather to return home after 15 years in Siberia. Nelsons later studied conducting at the St. Petersburg Conservatory under an old Soviet maestro. He understands Shostakovich as few conductors do, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra clearly finds him inspiring. I have loved the BSO's self-produced recordings for years, but it's wonderful to see them again on the prestigious "yellow label," DGG. As expected, the recorded sound is demonstration quality.

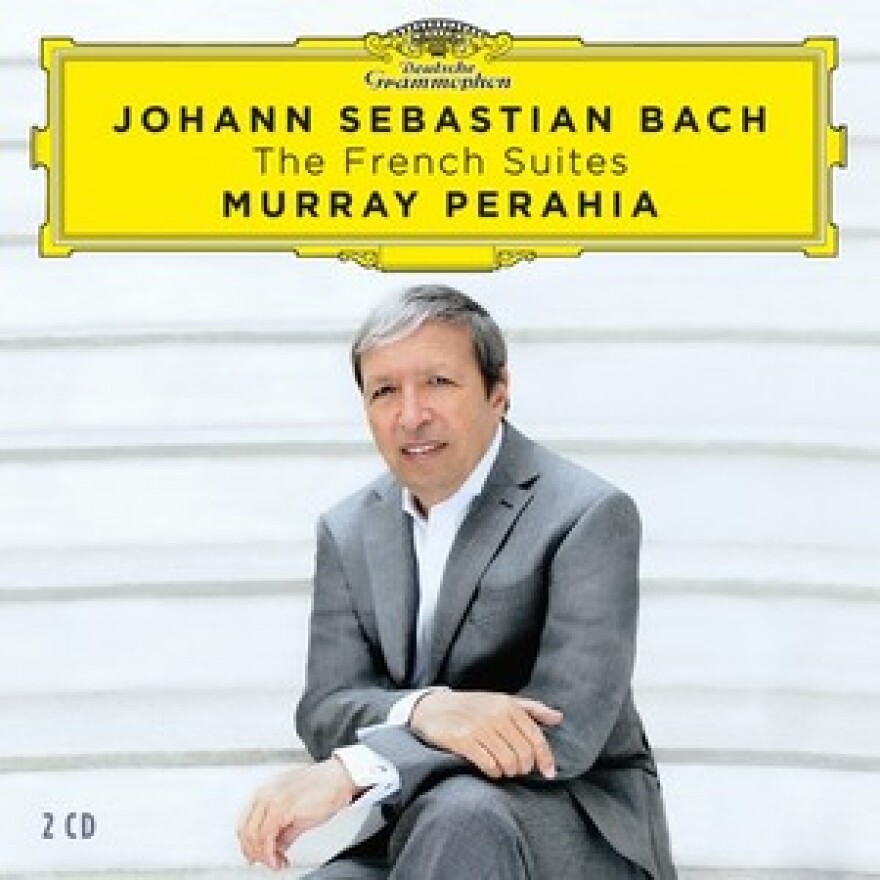

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: French Suites - Murray Perahia, piano (Deutsche Grammophon 479 6565) I've felt for a while that we live in a golden age of Bach playing, and gained confidence in the feeling when the not-easily-impressed David Hurwitz said the same in print. We can count the 2016 meta-mega-list as evidence. No fewer than thirty recordings of Bach's music made someone’s list, about 5% of all the recordings that received at least one vote. The preponderance of Bach conveys how much musicians wanted to record his music and how many of them did it superbly.

The sheer number of Bach recordings made it hard for any one to make the meta-list, yet one release stood out, and it shows that sometimes things go right in the world. It featured the great American pianist Murray Perahia.

After recovering from a hand injury that almost ended his career, Perahia recorded some of the greatest Bach on record for Sony. Now 70 years old, in 2016 he made his first recording for Deutsche Grammophon, and his playing is better than ever. If you love Bach, be sure to hear it. It will remind you, among other things, that the French Suites include some of Bach’s most profound music.

During the time he was separated from the piano, Perahia says, what kept him sane was studying Bach's scores. He became fascinated by Bach's use of harmonic tension (a skill Bach's sons referred to in his obituary), and in these suites I've never before felt the expressive power of the dissonant notes so fully. Perahia also internalized a feeling for the Baroque idioms that Bach references throughout these suites. For example, in the canarie-style Gigue from the Second Suite, David Schulenberg warns that "the skipping rhythm is heard almost without a break" so that "there is a danger of rhythmic monotony," but with Perahia you instead feel exhilarated.

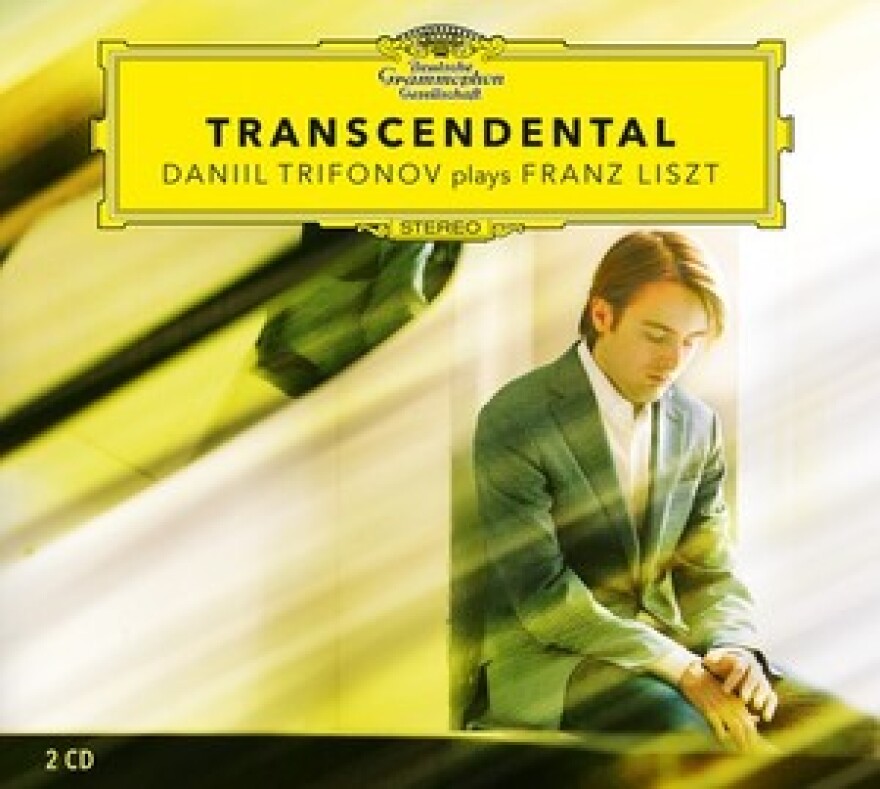

FRANZ LISZT: TRANSCENDENTAL - Transcendental Etudes, Paganini Etudes, and Concert Etudes - Daniil Trifonov, piano (Deutsche Grammophon 479 552) Speaking of golden ages, Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times has applied the phrase to today's piano players. In the past, he said, piano lovers often had to choose between artists with stupendous technique and those with profound insight, but today dozens of pianists offer both. A recent example is 25-year-old Daniil Trifonov, whose seemingly magical touch makes a piano sound so ravishing that it transcends the physics of hammers and strings, but whose brain seems to understand perfectly why the composers chose the notes they did. (Unlike the stereotypical virtuoso, Trifonov is finishing a doctorate in composition in Cleveland.) You don't have to know much about Liszt to be enchanted by the sheer beauty of the sounds conjured. You might wonder how many music writers know our Liszt etudes well enough to judge this album against Kyrill Gerstein's 2016 recording on the indie Myrios label. Jed Distler, who knows these pieces profoundly, preferredGerstein musically, while other knowledgeable critics preferred Trifonov, and the New York Times solved the problem by listing both in its end-of-year roundup. I like that solution. Classical musicians compete with each other as well as with a record catalog going back decades, and I wish there were a way not to have to compare varieties of excellence. That is exactly what we are forced to do by tournaments like "best-of-the-year" lists, so, like the NYT, let this one acknowledge both artists.

JEAN SIBELIUS: Symphonies nos. 3, 6, and 7 - Minnesota Orchestra conducted by Osmo Vanska (BIS 2006) With their then-new Finnish music director Osmo Vanska, the Minnesota Orchestra gained international prominence when the Swedish audiophile label BIS recorded them in a Beethoven cycle. Next up was Finland's most influential composer, Sibelius. BIS had recorded his symphonies with Vanska in the Nineties with Finland's leading orchestra, the Lahti, and many considered that set a modern reference. So why would BIS spring for another go-round? Perhaps sound recording continues to advance, or because BIS is known for taking risks, or because Vanska had been rethinking the works. The new cycle started well, but then was endangered when the orchestra fell into thelongest labor dispute in the history of major American orchestras - a 15-month lockout that led to cancelation of a Carnegie Hall gig and a European tour. Happily, our neighbors to the North eventually resolved the standoff, and you can consider this final disk in the new Sibelius series the comeback. The back-story itself could make it a sentimental favorite, but the interpretations are by no means routine. The flow and the atmosphere gripped many listeners worldwide, even in a couple of movements with notably unhurried tempos. The engineering is, sure enough, rich and realistic, with a dynamic range so wide that it will preclude listening in a moving car.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis - Laura Aikin (soprano), Bernarda Fink (mezzo), Johannes Chum (tenor), Ruben Drole (bass), Arnold Schoenberg Choir and the Concentus Musicus Wien conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Sony) - "From the heart, may it go to the heart," wrote Beethoven over the score of his Missa Solemnis, which he regarded as his greatest work. But performances can sound shrill and disjointed. Not here. The conductor, who has recorded it twice before, unifies it here in a way that is rare.

Harnoncourt founded the Concentus Musicus in 1953 to play early music on period instruments. By the 1980s he was conducting major orchestras, bringing iconoclastic imagination and ideas to every performance. Before his death last year at the age of 86, Harnoncourt asked that his final release be the tape of a 2015 concert of this Missa Solemnis. He'd recorded the work before with modern-instrument groups, but here returned to it with the Concentus Musicus, a much more virtuosic ensemble today than 50 years ago, and found new depths in it. You can hear why Harnoncourt wanted this release to be his final testament, as it is a kind of summation of his life's work. The Missa Solemnis contains some of Beethoven's greatest moments but for me, rarely gels as a totality. In this live performance it did, and I'm glad Sony released it commercially.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART: Don Giovanni - Karina Gauvin (Donna Elvira), Christina Gansch (Zerlina), Mika Kares (Commmendatore), Guido Loconsolo (Masetto), Kenneth Tarver (Don Ottavio), Vito Priante (Leporello), Myrto Papatanasiu (Donna Anna), Dimitris Tiliakos (Don Giovanni), Musica Aeterna conducted by Teodor Currentzis (Sony) - In 2005, Greek-born Russian conductor Teodor Currentzis, a self-described "anarchist narcissist" and "crazy genius, said, "I am going to save classical music. Give me five or ten years. You'll see." The decade is up, and you can decide for yourself what we've seen. But Currentzis did release, in 2016, a recording that ten critics put on their favorites list. It's of the greatest of operas about an anarchistic narcissist, Mozart's Don Giovanni.

Having funding helped. Currentzis directs the Opera and Ballet in the Ural city of Perm (which the USSR once called "Molotov"), and seems to be generously funded. Opera is the most expensive of art forms, and Currentzis's recording sessions are three-week-long residential intensives preceded by endless rehearsals. When recording Don Giovanni, according to PRI's The World said,singer Simone Kermes "seemed a bit dazed after more than 50 takes of a short passage," and said, "Of course Mozart is difficult to record and what Teodor wants, it's like over what a human can do... He has no respect [for] the singer. Sometimes I hate him."

As it turned out, Currentzis wasn't happy with that recording, and here Sony's deep corporate pockets gave him what few artist ever get: a do-over. Sony canned the first recording and funded a second intensive (Kermes was surely relieved not to be involved). Some critics found the final result too crazy, but ten of them loved its edginess.

COMING SOON: As I mentioned, the "long tail" was even more fascinating than the top picks. Did it include any women composers? How much Bach WAS there? What other new works? Stay tuned... I promised to post the rest soon, along with some notes on my methods and a complete list of sources!